Automatic Feature Matching and Image-stitching

Introduction

When morphing images together, hand-picking point correspondences each time may be a time consuming job. Therefore, devising an automatic feature detecting and homography computing technique is vital for image stitching. In the parts below, we will go in details about the process of picking point correspondences, devising affine transformation matrix from matched features, and creating mosaic from several images.

The parts below are inspired by “Multi-Image Matching using Multi-Scale Oriented Patches” by Brown et al.

First Step of Feature Point Detection: Harris Corners

Since we are automatically generating feature correspondences, we must first retrieve points in the image that have sufficient "context". Such points usually apprear at "corners" of the image. There are multiple ways to identify a point as "corner", and we'll focus on one of the definitions in this project: Harris Corners.

A point is defined as a Harris Corner if: given a window of pixels around the point, moving the window in all directions would result in a significant change of context. Expressed mathematically, Harris Corner occurs at

To simplify the expression of

Therefore, it suffices to know that a point

During our actual implementation of coarse search of feature points, we first calculate

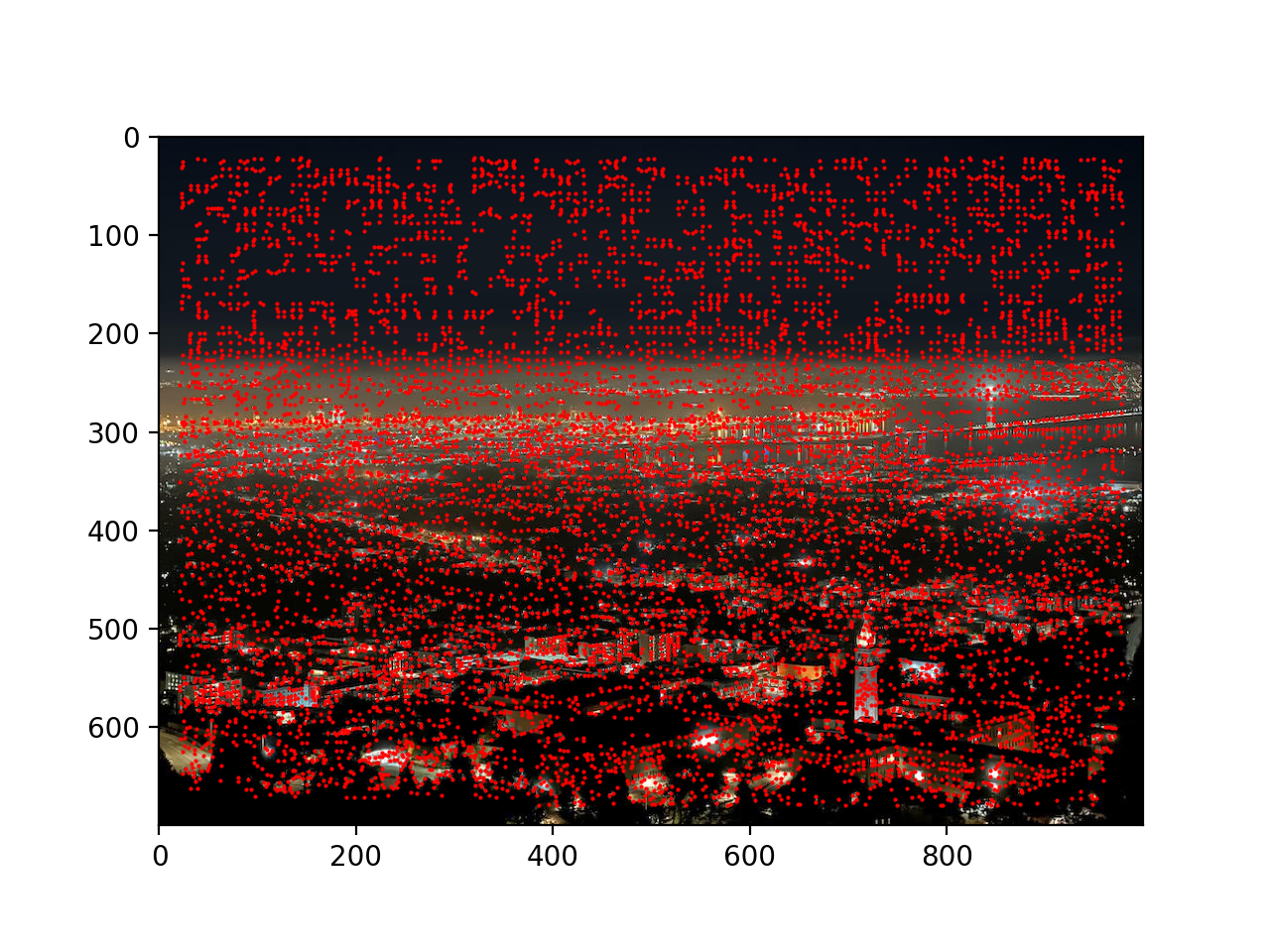

Below is a picture of the night Berkeley Bay from Lawrence Berkeley Lab, as well as coarse image features found on the image.

Original image:

Coarse feature points:

Second Step of Feature Point Detection: Non-max Suppression

As we may notice from the previous section, taking the local maxima within a

Theoretically, we will initialize a disk with large radius

In practice, we can use a robust algorithm to filter out the desired feature points. In particular, the maximum-suppression radius

where

If no feature point is found in the image with corner strength greater than

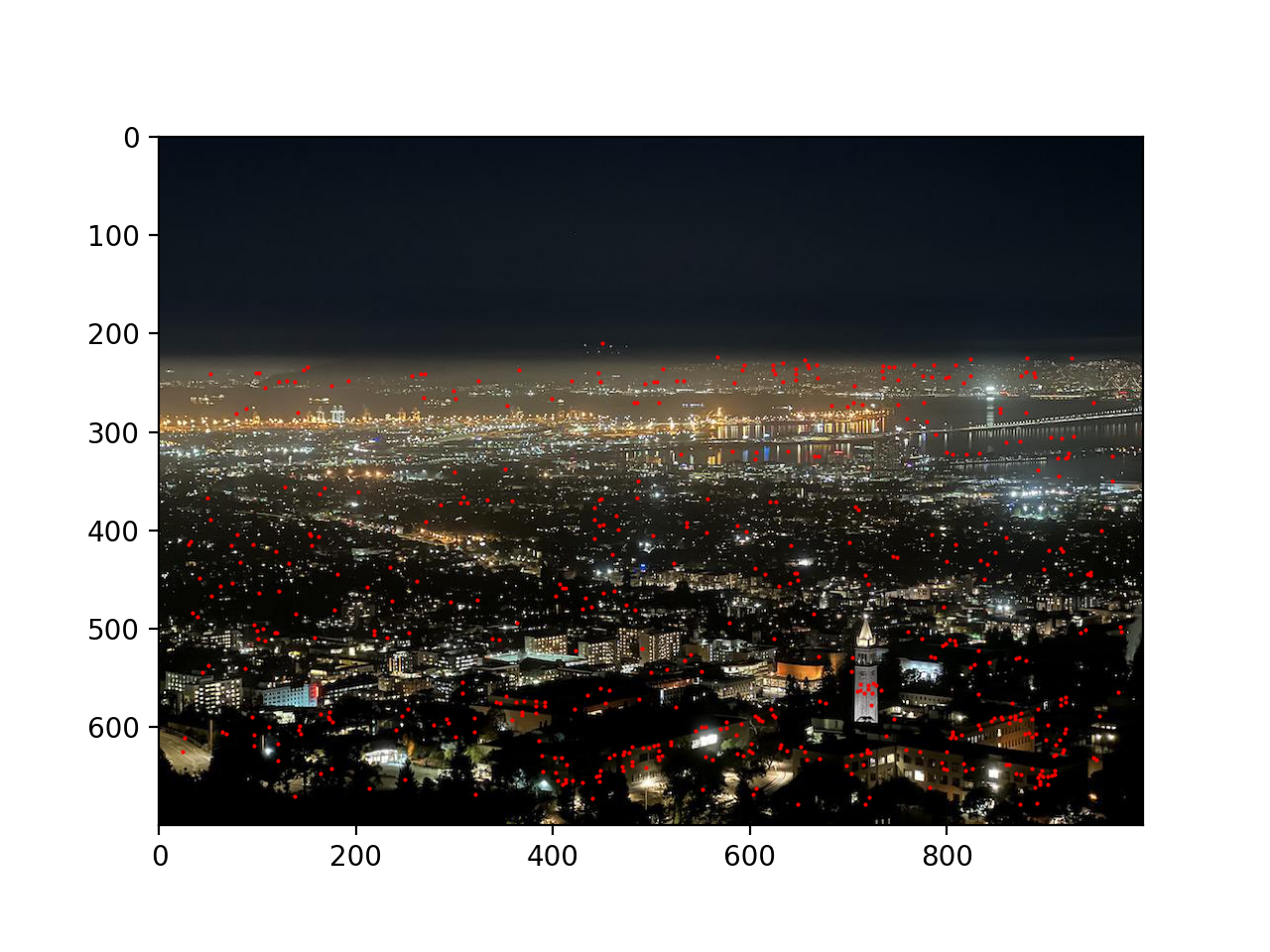

Below is the location of top 500 candidate feature points in the night Berkeley Bay photo:

Non-max suppressed feature points:

Extracting Features

In order to match point correspondences between two images, only knowing locations of feature points is not enough. We also need to know the "context" of each feature point to match them together. In order to make context extraction less sensitive to exact feature location, we will force sampling to be at a lower frequency than where the feature point is located. In other words, we will consider a patch of pixels around the feature point that will together determine its context.

According to the experiments conducted by Brown et al., we use an

Feature Matching

Next we will use the extracted feature context to match feature points between two images. A naive method is to iterate through all feature points in one image, and for each feature point, find out the feature point in the other image that has the closest context. However, the naive approach will force the algorithm to find a matching for each feature point, which is typically not the case when we create a mosaic from two images with different views (e.g.: feature points on the left half of the left view can never match with feature points in the right view, since the left half of the left view can never appear in the right view).

In order to remedy potential over-matching, we have to find ways to filter out the points that can never be matched. To approach this problem, we can first think about the property of a pair of matching feature points: the difference of context around those two points should be significantly smaller than that of other candidate pairs.

With this knowledge in hand, we can devise a more accurate method of detecting feature matchings. For every feature point in the first image, we calculate its context difference with every feature points in the second image. We then pick the smallest distance that corresponds to the best match. We also pick the second smallest distance to be the suboptimal match. Taking the ratio of these two distances (

According to experiments conducted by Brown et al., we use

RANSAC: Computing Homography

Although we have filtered out most outlier points with no matches, we still cannot guarantee that the remaining points all produce valid matchings that can be directly applied to calculating the affine transformation matrix. In other words, we have to further filter out outliers for accurate homography computation. Here we will apply a method called RANdom SAmple Consensus (or RANSAC).

The workflow of RANSAC is to first assume that all feature pairs are valid. This would mean that randomly picking four of them would result in a good enough homography, which can map all feature points in one image to roughly their corresponding locations as the second image. If this is not the case, then some outliers must appear in either our chosen points or in the remaining points.

To implement the RANSAC method, we will generate groups of

Putting Altogether: Automatic Image Stitching

The above sections have provided a detailed overview of how automatic feature detection and homography computation work. Putting all the techniques together, we can implement automatic image stitching.

Below we show three groups of mosaics, computed both automatically and manually. We can see that the automatic approach achieves roughly the same effect as the manual approach.

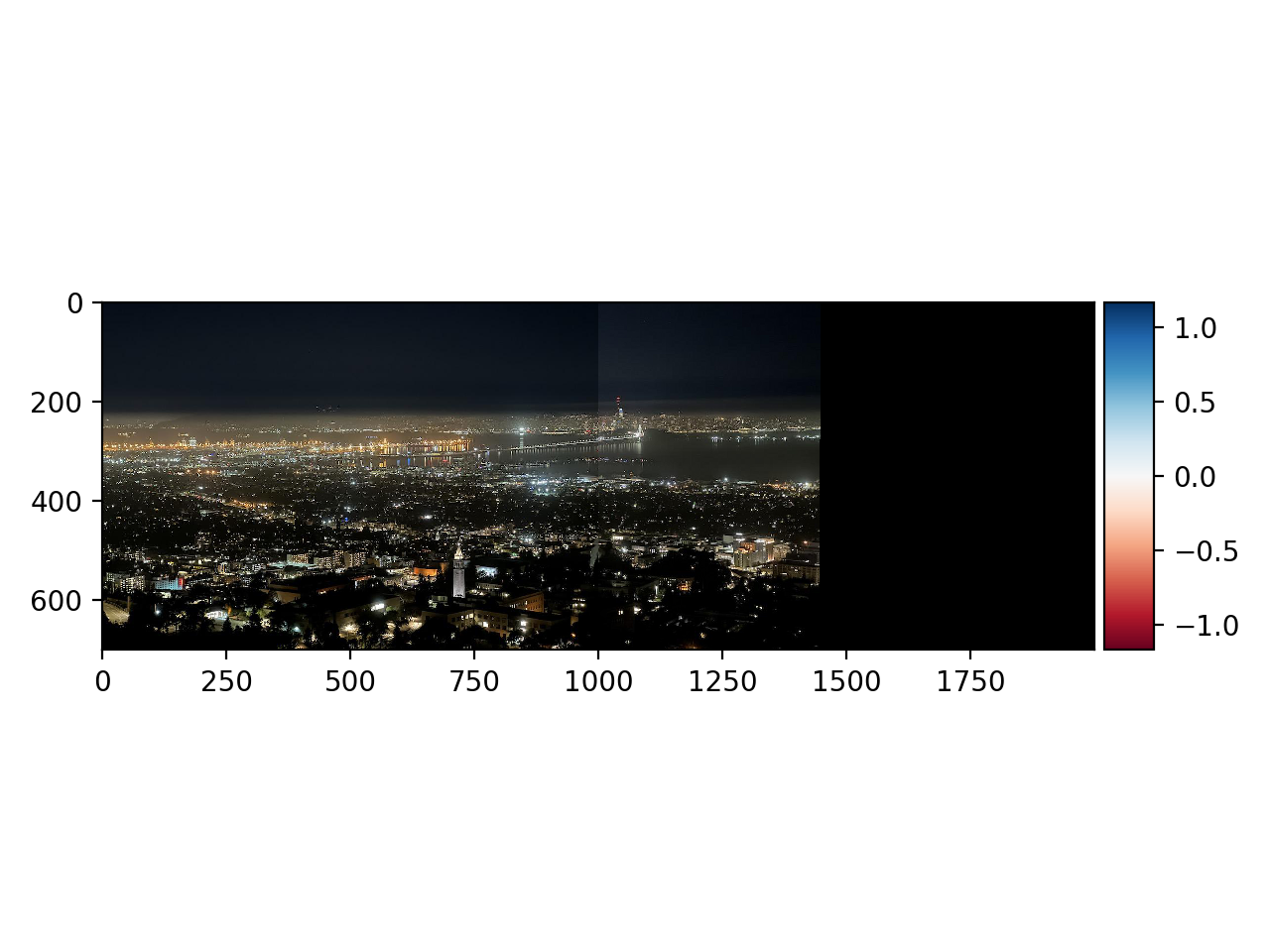

Goup One: Night Berkeley Bay

Original left image:

Original right image:

Unmasked automatic result:

Masked automatic result:

Unmasked manual result:

Masked manual result:

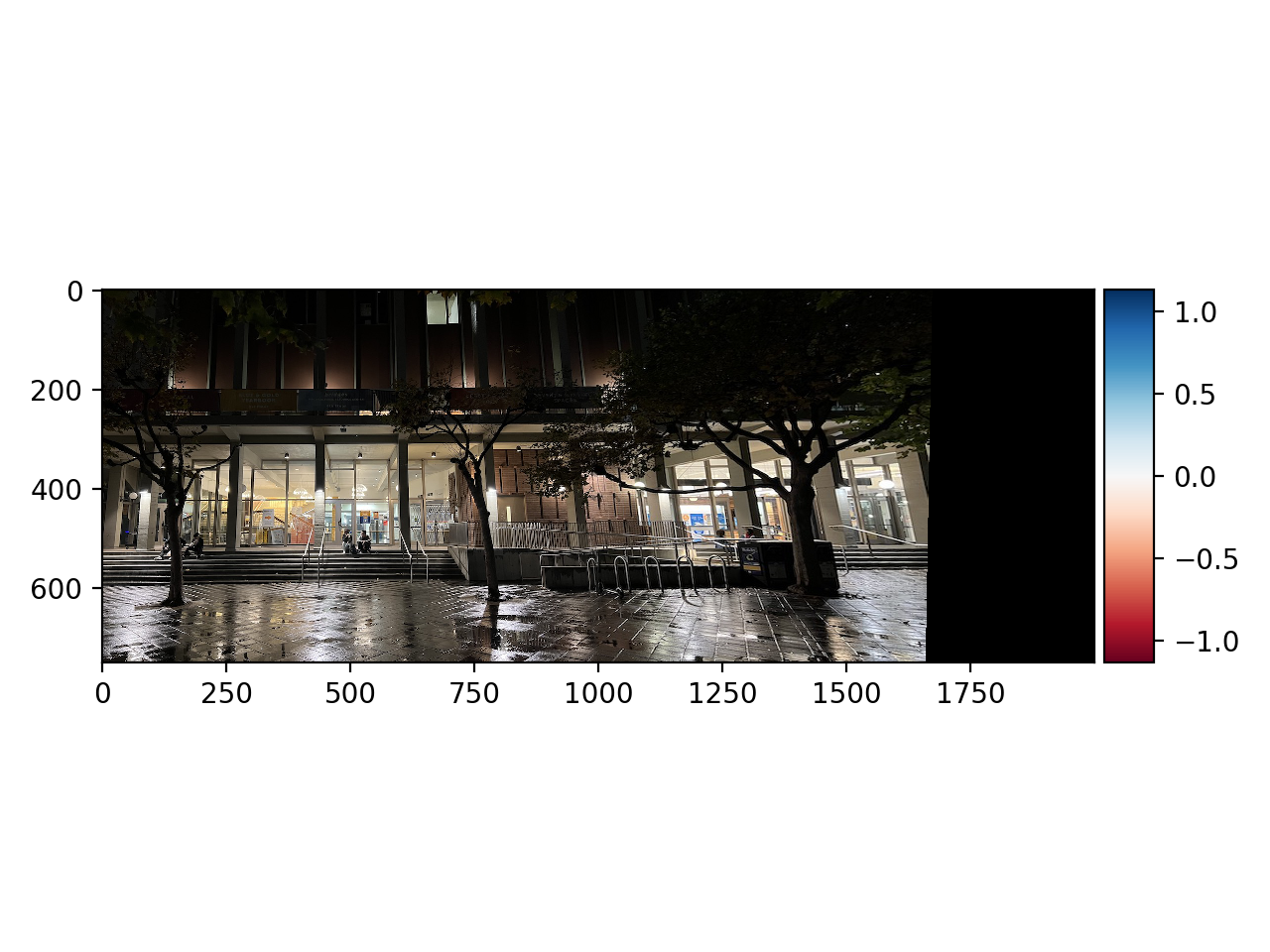

Group Two: MLK

Original left image:

Original right image:

Unmasked automatic result:

Masked automatic result:

Unmasked manual result:

Masked manual result:

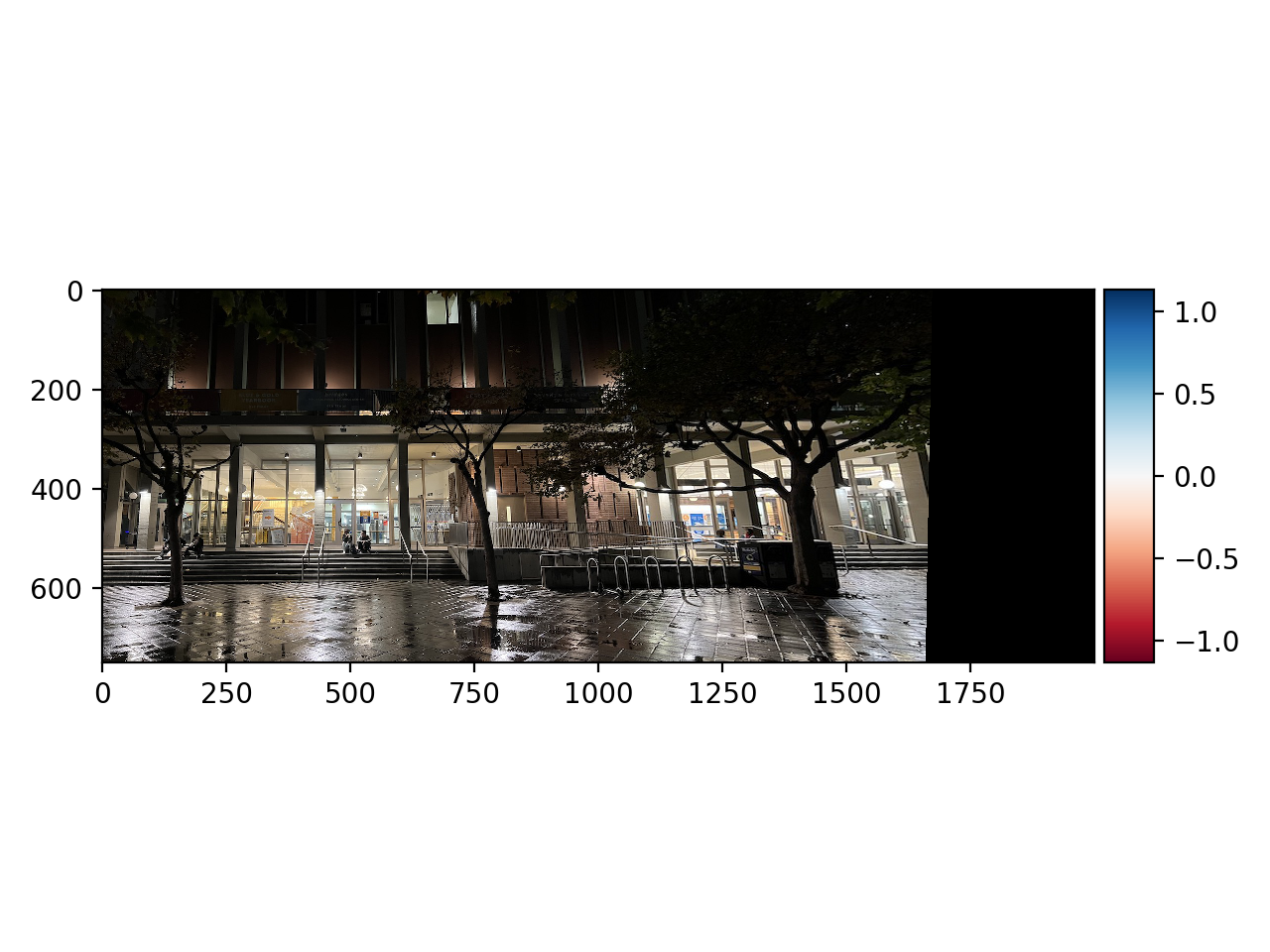

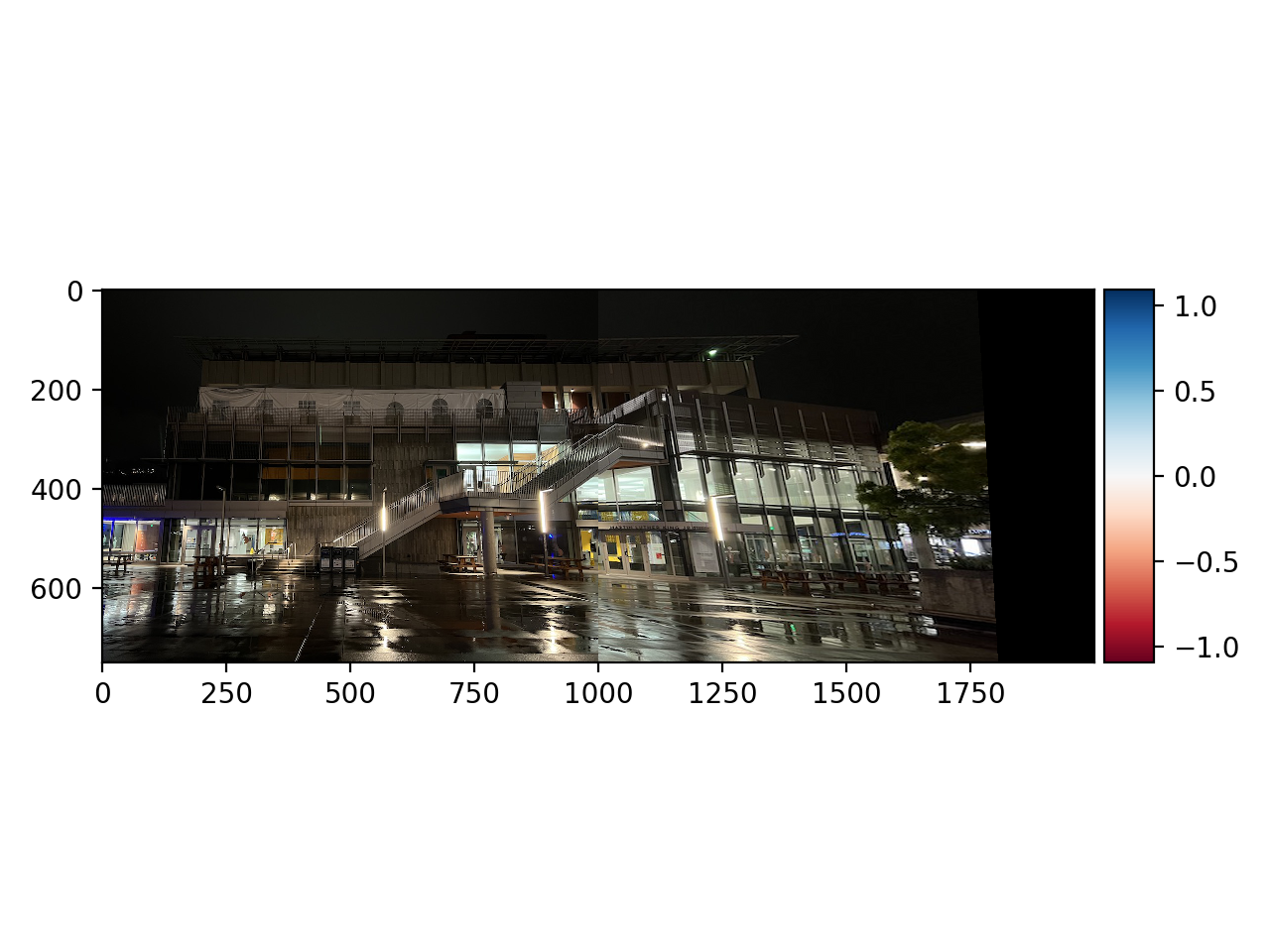

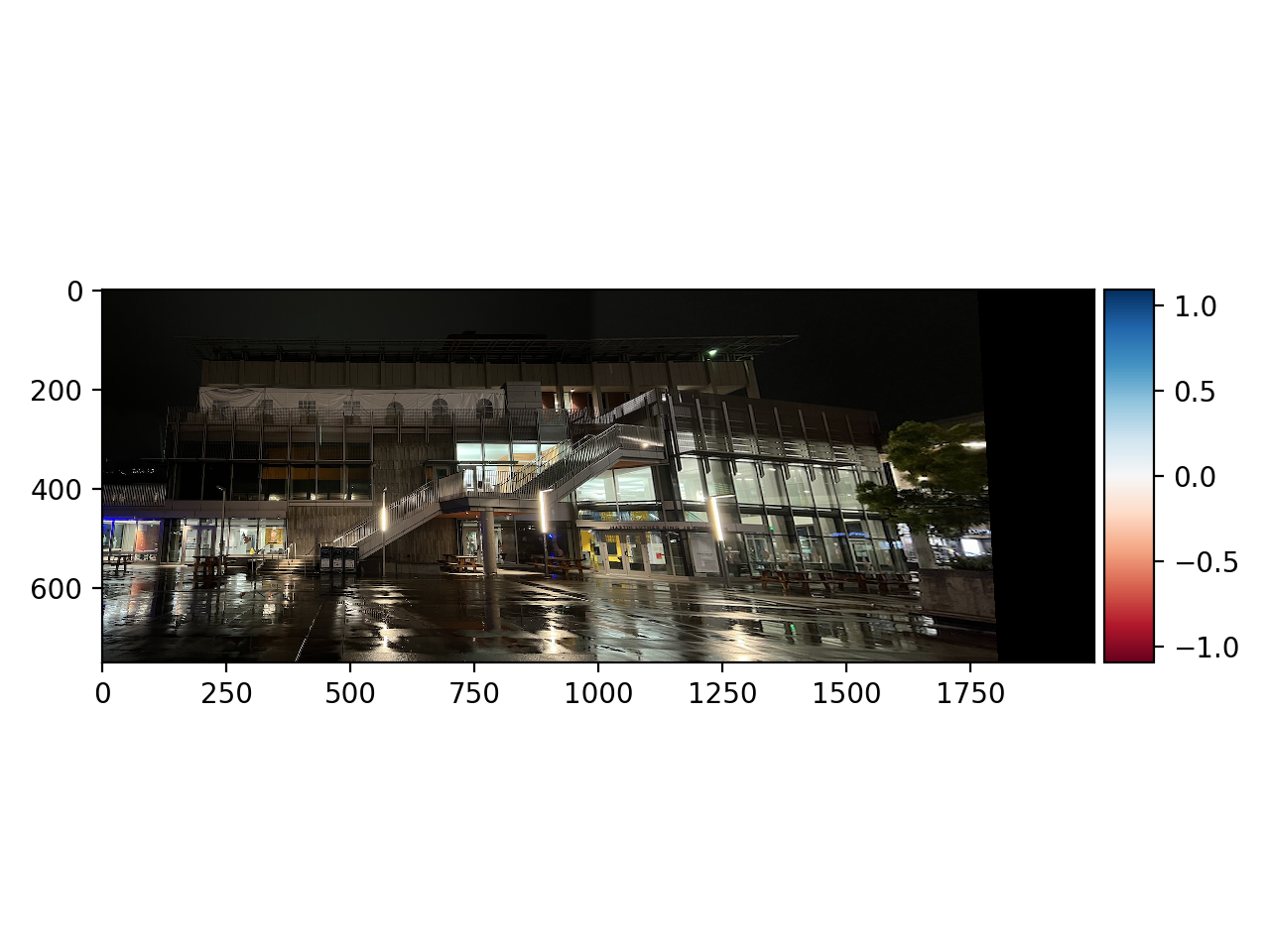

Group Three: Zellerbach Hall

Original left image:

Original right image:

Unmasked automatic result:

Masked automatic result:

Unmasked manual result:

Masked manual result: