Discussion 11: Scheme, Scheme Lists

Introduction

In the next part of the course, we will be working with the Scheme programming language. In addition to learning how to write Scheme programs, we will eventually write a Scheme interpreter in Project 4!

Scheme is a famous functional programming language from the 1970s. It is a dialect of Lisp (which stands for LISt Processing). The first observation most people make is the unique syntax, which uses a prefix notation and (often many) nested parentheses (see http://xkcd.com/297/). Scheme features first-class functions and optimized tail-recursion, which were relatively new features at the time.

Primitives and Defining Variables

Scheme has a set of atomic primitive expressions. Atomic means that these expressions cannot be divided up.

scm> 123

123

scm> #t

True

scm> #f

FalseUnlike in Python, the only primitive in Scheme that is a false value is

#f and its equivalents, false and False. This means that 0 is not false.

In Scheme, we can use the define special form to bind values to symbols, which we can then use as variables. When a symbol is defined this way, the define special form returns the symbol.

(define <variable name> <value>)

Evaluates <value> and binds the value to <variable name> in the current environment.

WWSD

scm> (define a 1)scm> ascm> (define b a)scm> bscm> (define c 'a)scm> cCall Expressions

Call expressions apply a procedure to some arguments.

(<operator> <operand1> <operand2> ...)Call expressions in Scheme work exactly like they do in Python. To evaluate them:

- Evaluate the operator to get a procedure.

- Evaluate each of the operands from left to right.

- Apply the value of the operator to the evaluated operands.

For example, consider the call expression (+ 1 2). First, we evaluate

the symbol + to get the built-in addition procedure. Then we evaluate

the two operands 1 and 2 to get their corresponding atomic

values. Finally, we apply the addition procedure to the values 1 and

2 to get the return value 3.

Operators may be symbols, such as + and *, or more

complex expressions, as long as they evaluate to procedure values.

Here is a reference for the Scheme Built-In Procedures.

scm> (- 1 1) ; 1 - 1

0

scm> (* (+ 1 2) (+ 1 2)) ; (1 + 2) * (1 + 2)

9WWSD

What would Scheme display? As a reminder, the built-in quotient function performs floor division.

scm> (define a (+ 1 2))scm> ascm> (define b (- (+ (* 3 3) 2) 1))scm> (+ a b)scm> (= (modulo b a) (quotient 5 3))Special Forms

Special form expressions contain a special form as the operator. Special form expressions do not follow the same rules of evaluation as call expressions. Each special form has its own rules of evaluation -- that's what makes them special! Here's the Scheme Specification to reference the special forms we will cover in this class.

It is important to note that everything in Scheme is either an atomic or an expression, so although these special forms look and operate similarly to Python, they are evaluated differently.

Special forms like if, cond, and, or in Python direct the control flow of a program and allow you to evaluate specific expressions under some condition. In Scheme, however, these special forms are expressions that take in a set amount of parameters and return some value based on the condition passed in.

If Expression

An if expression looks like this:

(if <predicate> <if-true> [if-false])

<predicate> and <if-true> are required expressions and

[if-false] is optional.

The rules for evaluation are as follows:

- Evaluate

<predicate>. - If

<predicate>evaluates to a truth-y value, evaluate<if-true>and return its value. Otherwise, evaluate[if-false]if provided and return its value.

if is a special form as not all of its operands will be evaluated. The value of the first operand determines whether the second or the third operator is evaluated.

Important: Only

#fis a false-y value in Scheme; everything else is truth-y, including0.

scm> (if (< 4 5) 1 2)

1

scm> (if #f (/ 1 0) 42)

42Cond Expression

A cond expression looks like this:

(cond (<pred1> <if-pred1>) (<pred2> <if-pred2>) ... (<predn> <if-predn>) [(else <else-expression>)])

Must have at least one <predn> and <if-predn> and

[(else <else-expression>)] is optional.

The rules for evaluation are as follows:

- Evaluate the predicates

<pred1>,<pred2>, ...,<predn>in order until you reach one that evaluates to a truth-y value. - If you reach a predicate that evaluates to a truth-y value, evaluate and return the corresponding expression in the clause.

- If none of the predicates are truth-y and there is an else clause, evaluate and return

<else-expression>.

cond is a special form because it does not evaluate its operands in their entirety; the predicates are evaluated separately from their corresponding return expression. In addition, the expression short circuits upon reaching the first predicate that evaluates to a truth-y value, leaving the remaining predicates unevaluated.

scm> (cond

((< 4 5) 1)

(else 2)

)

1

scm> (cond

(#f (/ 1 0))

(else 42)

)

42Let Expressions

A let expression looks like this:

(let ([binding_1] ... [binding_n]) <body> ...)

Each binding corresponds to expressions of the form (<name> <expression>).

Scheme evaluates a let expression using the following steps:

- Create a new local frame that extends the current environment (in other words, it creates a new child frame whose parent is the current frame).

- For each

bindingprovided, bind eachnameto its corresponding evaluatedexpression. - Finally, the

bodyexpressions are evaulated in order in this new frame, returning the result of evaluating the last expression.

Note that bindings are optional within a let statement, but we typically include them.

scm> (let (

(x 5)

(y 10)

)

(print x)

(print y)

(- x y)

(+ x y)

)

5

10

15Note that (- x y) in the body of this let expression does get evaluated, but the result doesn't get returned by the let expression because

only the value of the last expression in the body, (+ x y), gets returned. Thus, the interpreter does not display -5 (the result of (- x y)).

However, we see that 5 and 10 are displayed out by the interpreter. This is because printing 5 and printing 10 were side effects

of evluating the expressions (print x) and (print y), respectively. 5 and 10 are not the return values of (print x) and (print y).

Begin Expressions

A begin expression looks like this: (begin <body_1> ... <body_n>)

Scheme evaluates a begin expression by evaluating each body in order in the current environment, returning the result of evaluating the last body.

scm> (begin

(print (< 2 3))

(print 'hello)

(+ 1 2)

(- 5 7)

)

#t

hello

-2Again, note that (+ 1 2) does get evaluted, but the result, 3, does not get returned by the begin expression (and thus does not get displayed by the interpreter) because it is not the last body expression.

Boolean operators

Like Python, Scheme has the boolean operators and,

or, and not. and and or are

special forms because they are short-circuiting operators,

while not is a builtin procedure.

andtakes in any amount of operands and evaluates these operands from left to right until one evaluates to a false-y value. It returns that first false-y value or the value of the last expression if there are no false-y values.oralso evaluates any number of operands from left to right until one evaluates to a truth-y value. It returns that first truth-y value or the value of the last expression if there are no truth-y values.nottakes in a single operand, evaluates it, and returns its opposite truthiness value.

scm> (and 25 32)

32

scm> (or 1 (/ 1 0)) ; Short-circuits

1

scm> (not (odd? 10))

#tWWSD

What would Scheme display?

scm> (if (or #t (/ 1 0)) 1 (/ 1 0))scm> ((if (< 4 3) + -) 4 100)scm> (cond

((and (- 4 4) (not #t)) 1)

((and (or (< 9 (/ 100 10)) (/ 1 0)) #t) -1)

(else (/ 1 0))

)scm> (let (

(a (- 3 2))

(b (+ 5 7))

)

(* a b)

(if (< (+ a b) b)

(/ a b)

(/ b a)

)

)scm> (begin

(if (even? (+ 2 4))

(print (and 2 0 3))

(/ 1 0)

)

(+ 2 2)

(print 'lisp)

(or 2 0 3)

)Defining Functions

All Scheme procedures are constructed as lambda procedures.

One way to create a procedure is to use the lambda special form.

(lambda (<param1> <param2> ...) <body>)

This expression creates a lambda function with the given parameters and body,

but does not evaluate the body. As in Python, the body is not

evaluated until the function is called and applied to some argument

values. The fact that neither the parameters nor the body is evaluated is what

makes lambda a special form.

We can also assign the value of an expression to a

name with a define special form:

(define (<name> <param> ...) <body> ...)(define <name> (lambda (<param> ...) <body> ...))

These two expressions are equivalent; the first is a concise version of the second.

scm> ; Bind lambda function to square

scm> (define square (lambda (x) (* x x)))

square

scm> (define (square x) (* x x)) ; Same as above

square

scm> square

(lambda (x) (* x x))

scm> (square 4)

16Q1: Virahanka-Fibonacci

Write a function that returns the n-th Virahanka-Fibonacci number.

scm> (vir-fib 0)

0

scm> (vir-fib 1)

1

scm> (vir-fib 10)

55Pairs and Lists

All lists in Scheme are linked lists. Scheme lists are composed of two element pairs. We define a list as being either

- the empty list,

nil - a pair whose second element is a list

As in Python, linked lists are recursive data structures. The base case is the empty list.

We use the following procedures to construct and select from lists:

(cons first rest)constructs a list with the given first element and rest of the list. For now, ifrestis not a pair ornilit will error.(car lst)gets the first item of the list(cdr lst)gets the rest of the list

To visualize Scheme lists, you can use the draw function in code.cs61a.org.

scm> nil

()

scm> (define lst (cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 nil))))

lst

scm> lst

(1 2 3)

scm> (car lst)

1

scm> (cdr lst)

(2 3)Scheme lists are displayed in a similar way to the Link class we defined in Python. Here is an example in 61A Code.

Two other ways of creating lists are using the built-in list

procedure or the quote special form.

The list procedure has the syntax (list <item> ...). It takes in an arbitrary number of operands and constructs a list with their values.

scm> (list 1 2 3)

(1 2 3)The quote special form has the syntax (quote <expression>). It returns the literal expression without evaluating it.

A shorthand for the quote special form is '<expression>.

scm> (define a 61)

a

scm> a

61

scm> (quote a)

a

scm> 'a

aWe can use the quote form to create a list by passing in a combination as the expression:

scm> (quote (1 x 3))

(1 x 3)

scm> '(1 x 3) ; Equivalent to the previous quote expression

(1 x 3)An important difference between list (along with cons) and quote is that list and cons evaluate each of their operands before putting them into a list, while quote will return the list exactly as typed, without evaluating any of the individual elements.

scm> (define a 1)

a

scm> (define b 2)

b

scm> (list a b 3)

(1 2 3)

scm> '(a b 3)

(a b 3)Note that if we wanted to create the list (a b 3) using the list procedure, we could quote the symbols a and b so that they are not evaluated

when making the list:

scm> (list 'a 'b 3)

(a b 3)=, eq?, equal?

(= <a> <b>)returns true ifaequalsb. Both must be numbers.(eq? <a> <b>)returns true ifaandbare equivalent primitive values. For two objects,eq?returns true if both refer to the same object in memory. Similar to checking identity between two objects usingisin Python(equal? <a> <b>)returns true ifaandbare pairs that have the same contents (cars andcdrs are equivalent). Similar to checking equality between two lists using==in Python. Ifaandbare not pairs,equal?behaves likeeq?.

scm> (define a '(1 2 3))

a

scm> (= a a)

Error

scm> (equal? a '(1 2 3))

#t

scm> (eq? a '(1 2 3))

#fWWSD

What would Scheme display?

scm> (cons 1 (cons 2 nil))scm> (car (cons 1 (cons 2 nil)))scm> (cdr (cons 1 (cons 2 nil)))scm> (list 1 2 3)scm> '(1 2 3)scm> (cons 1 '(list 2 3)) ; Recall quotingscm> '(cons 4 (cons (cons 6 8) ()))scm> (cons 1 (list (cons 3 nil) 4 5))Q2: List Making

Let's make some Scheme lists. We'll define the same list with list, quote, and cons.

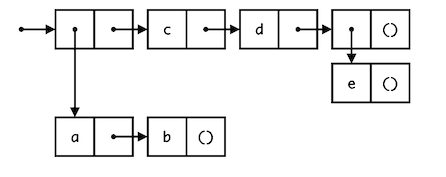

The following list was visualized using the draw feature of code.cs61a.org.

First, use list:

Now use quote. What differences are there?

Now try with cons. For convenience, we've defined a helpful-list and another-helpful-list:

Q3: List Concatenation

Write a function which takes two lists and concatenates them.

Notice that simply calling (cons a b) would not work because it will

create a deep list. Do not call the builtin procedure append, since it

does the same thing as list-concat should do.

scm> (list-concat '(1 2 3) '(2 3 4))

(1 2 3 2 3 4)Q4: Remove

Implement a procedure remove that takes in a list and returns a new list with

all instances of item removed from lst. You may assume the list will only

consist of numbers and will not have nested lists.

Run in 61A CodeHint: You might find the built-in

filterprocedure useful (though it is definitely possible to complete this question without it).You can find information about how to use

filterin the 61A Scheme builtin specification!

Additional Practice

Q5: List Duplicator

Write a Scheme function, duplicate that, when given a list, such as (1 2 3 4),

duplicates every element in the list (i.e. (1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4)).