Discussion 11: Tail Recursion, Scheme, Regular Expressions

More Scheme!

Questions

Q1: Greatest Common Divisor

The GCD is the the greatest common divisor of two numbers.

Write the procedure gcd, which computes the GCD of numbers a and b.

Recall that Euclid's Algorithm tells us that the GCD of two values is either of

the following:

- the smaller value if it evenly divides the larger value, or

- the greatest common divisor of the smaller value and the remainder of the larger value divided by the smaller value

In other words, if a is greater than b and a is not divisible by

b, then

gcd(a, b) = gcd(b, a % b)Run in 61A CodeYou may find the provided procedures

minandmaxhelpful. You can also use the built-inmoduloandzero?procedures.scm> (modulo 10 4) 2 scm> (zero? (- 3 3)) #t scm> (zero? 3) #f

Q2: Leaves

Here is a Binary Tree ADT in Scheme:

(define (make-btree label left right)

(cons label (cons left right)))

(define (label tree)

(car tree))

(define (left tree)

(car (cdr tree)))

(define (right tree)

(cdr (cdr tree)))

(define test-tree

(make-btree 2

(make-btree 1

nil

nil)

(make-btree 4

(make-btree 3

nil

nil)

nil)))

; test-tree:

; 2

; / \

; 1 4

; /

; 3Write a procedure num-leaves that counts the number of leaves in a

tree.

Tail Recursion

When writing a recursive procedure, it's possible to write it in a tail recursive way, where all of the recursive calls are tail calls. A tail call occurs when a function calls another function as the last action of the current frame.

Consider this implementation of factorial that is not tail recursive:

(define (factorial n)

(if (= n 0)

1

(* n (factorial (- n 1)))))The recursive call occurs in the last line, but it is not the last expression

evaluated. After calling (factorial (- n 1)), the function still needs to

multiply that result with n. The final expression that is evaluated is

a call to the multiplication function, not factorial itself. Therefore,

the recursive call is not a tail call.

Here's a visualization of the recursive process for computing (factorial 6) :

(factorial 6)

(* 6 (factorial 5))

(* 6 (* 5 (factorial 4)))

(* 6 (* 5 (* 4 (factorial 3))))

(* 6 (* 5 (* 4 (* 3 (factorial 2)))))

(* 6 (* 5 (* 4 (* 3 (* 2 (factorial 1))))))

(* 6 (* 5 (* 4 (* 3 (* 2 1)))))

(* 6 (* 5 (* 4 (* 3 2))))

(* 6 (* 5 (* 4 6)))

(* 6 (* 5 24))

(* 6 120)

720The interpreter first must reach the base case and only then can it begin to calculate the products in each of the earlier frames.

We can rewrite this function using a helper function that remembers the temporary product that we have calculated so far in each recursive step.

(define (factorial n)

(define (fact-tail n result)

(if (= n 0)

result

(fact-tail (- n 1) (* n result))))

(fact-tail n 1))fact-tail makes a single recursive call to fact-tail, and

that recursive call is the last expression to be evaluated, so it is a tail

call. Therefore, fact-tail is a tail recursive process.

Here's a visualization of the tail recursive process for computing (factorial 6):

(factorial 6)

(fact-tail 6 1)

(fact-tail 5 6)

(fact-tail 4 30)

(fact-tail 3 120)

(fact-tail 2 360)

(fact-tail 1 720)

(fact-tail 0 720)

720The interpreter needed less steps to come up with the result, and it didn't need to re-visit the earlier frames to come up with the final product.

Tail Call Optimization

When a recursive procedure is not written in a tail recursive way, the interpreter must have enough memory to store all of the previous recursive calls.

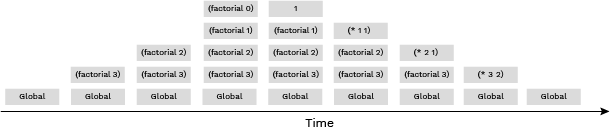

For example, a call to the (factorial 3) in the non tail-recursive version

must keep the frames for all the numbers from 3 down to the base case,

until it's finally able to calculate the intermediate products and forget those frames:

For non tail-recursive procedures, the number of active frames grows proportionally to the number

of recursive calls. That may be fine for small inputs, but imagine calling factorial

on a large number like 10000. The interpreter would need enough memory for all 1000 calls!

Fortunately, proper Scheme interpreters implement tail-call optimization as a requirement of the language specification. TCO ensures that tail recursive procedures can execute with a constant number of active frames, so programmers can call them on large inputs without fear of exceeding the available memory.

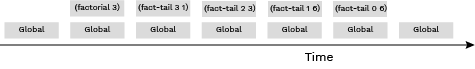

When the tail recursive factorial is run in an interpreter with tail-call optimization,

the interpreter knows that it does not need to keep the previous frames around,

so it never needs to store the whole stack of frames in memory:

Tail-call optimization can be implemented in a few ways:

- Instead of creating a new frame, the interpreter can just update

the values of the relevant variables in the current frame (like

nandresultfor thefact-tailprocedure). It reuses the same frame for the entire calculation, constantly changing the bindings to match the next set of parameters. - How our 61A Scheme interpreter works: The interpreter builds a new frame as usual, but then replaces the current frame with the new one. The old frame is still around, but the interpreter no longer has any way to get to it. When that happens, the Python interpreter does something clever: it recycles the old frame so that the next time a new frame is needed, the system simply allocates it out of recycled space. The technical term is that the old frame becomes "garbage", which the system "garbage collects" behind the programmer's back.

Tail Context

When trying to identify whether a given function call within the body of a function is a tail call, we look for whether the call expression is in tail context.

Given that each of the following expressions is the last expression in the body of the function, the following expressions are tail contexts:

- the second or third operand in an

ifexpression - any of the non-predicate sub-expressions in a

condexpression (i.e. the second expression of each clause) - the last operand in an

andor anorexpression - the last operand in a

beginexpression's body - the last operand in a

letexpression's body

For example, in the expression (begin (+ 2 3) (- 2 3) (* 2 3)),

(* 2 3) is a tail call because it is the last operand expression to be

evaluated.

Questions

Q3: Is Tail Call

For each of the following procedures, identify whether it contains a recursive call in a tail context. Also indicate if it uses a constant number of active frames.(define (question-a x)

(if (= x 0) 0

(+ x (question-a (- x 1)))))(define (question-b x y)

(if (= x 0) y

(question-b (- x 1) (+ y x))))(define (question-c x y)

(if (> x y)

(question-c (- y 1) x)

(question-c (+ x 10) y)))(define (question-d n)

(if (question-d n)

(question-d (- n 1))

(question-d (+ n 10))))(define (question-e n)

(cond ((<= n 1) 1)

((question-e (- n 1)) (question-e (- n 2)))

(else (begin (print 2) (question-e (- n 3))))))Q4: Sum

Write a tail recursive function that takes in a Scheme list and returns the numerical sum of all values in the list. You can assume that the list contains only numbers (no nested lists).scm> (sum '(1 2 3))

6

scm> (sum '(10 -3 4))

11Q5: Reverse

Write a tail-recursive function reverse that takes in a Scheme list a

returns a reversed copy. Hint: use a helper function!

scm> (reverse '(1 2 3))

(3 2 1)

scm> (reverse '(0 9 1 2))

(2 1 9 0)Regular Expressions

Regular Expressions

Regular expressions are a way to describe sets of strings that meet certain criteria, and are incredibly useful for pattern matching.

The simplest regular expression is one that matches a sequence of characters, like aardvark to match any "aardvark" substrings in a string.

However, you typically want to look for more interesting patterns. We recommend using an online tool like regexr.com for trying out patterns, since you'll get instant feedback on the match results.

Character classes

A character class makes it possible to search for any one of a set of characters. You can specify the set or use pre-defined sets.

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

[abc] |

Matches a, b, or c |

[a-z] |

Matches any character between a and z |

[^A-Z] |

Matches any character that is not between A and Z. |

\w |

Matches any "word" character. Equivalent to [A-Za-z0-9_] |

\d |

Matches any digit. Equivalent to [0-9]. |

[0-9] |

Matches a single digit in the range 0 - 9. Equivalent to \d |

\s |

Matches any whitespace character (spaces, tabs, line breaks). |

. |

Matches any character besides new line. |

Character classes can be combined, like in [a-zA-Z0-9].

Combining patterns

There are multiple ways to combine patterns together in regular expressions.

| Combination | Description |

|---|---|

AB |

A match for A followed immediately by one for B. Example: x[.,]y matches "x.y" or "x,y" |

A⎮B |

Matches either A or B. Example: \d+⎮Inf matches either a sequence containing 1 or more digits or "Inf" |

A pattern can be followed by one of these quantifiers to specify how many instances of the pattern can occur.

| Quantifier | Description |

|---|---|

* |

0 or more occurrences of the preceding pattern. Example: [a-z]* matches any sequence of lower-case letters or the empty string. |

+ |

1 or more occurrences of the preceding pattern. Example: \d+ matches any non-empty sequence of digits. |

? |

0 or 1 occurrences of the preceding pattern. Example: [-+]? matches an optional sign. |

{1,3} |

Matches the specified quantity of the preceding pattern. {1,3} will match from 1 to 3 instances. {3} will match exactly 3 instances. {3,} will match 3 or more instances. Example: \d{5,6} matches either 5 or 6 digit numbers. |

Groups

Parentheses are used similarly as in arithmetic expressions, to create groups. For example, (Mahna)+ matches strings with 1 or more "Mahna", like "MahnaMahna". Without the parentheses, Mahna+ would match strings with "Mahn" followed by 1 or more "a" characters, like "Mahnaaaa".

Anchors

^- Matches the beginning of a string. Example:

^(I⎮You)matches I or You at the start of a string.

- Matches the beginning of a string. Example:

$- Normally matches the empty string at the end of a string or just before a newline at the end of a string. Example:

(\.edu|\.org|\.com)$matches .edu, .org, or .com at the end of a string.

- Normally matches the empty string at the end of a string or just before a newline at the end of a string. Example:

\b- Matches a "word boundary", the beginning or end of a word. Example:

s\bmatches s characters at the end of words.

- Matches a "word boundary", the beginning or end of a word. Example:

Special characters

The following special characters are used above to denote types of patterns:

\ ( ) [ ] { } + * ? | $ ^ .

That means if you actually want to match one of those characters, you have to escape it using a backslash. For example, \(1\+3\) matches "(1 + 3)".

Using regular expressions in Python

Many programming languages have built-in functions for matching strings to regular expressions. We'll use the [Python re module] in 61A, but you can also use similar functionality in SQL, JavaScript, Excel, shell scripting, etc.

The search method searches for a pattern anywhere in a string:

re.search(r"(Mahna)+", "Mahna Mahna Ba Dee Bedebe")

That method returns back a match object, which is considered truth-y in Python and can be inspected to find the matching strings.

For more details, please consult the re module documentation or the re tutorial.

Questions

Q6: Meme-ified

In this question, we will identify whether a given message has been meme-ified, or uses sticky caps. A meme-ified message contains at least one instance of the following sequence: a capitalized letter, followed by a lowercase letter, followed by another capitalized letter. For example, the following string is not meme-ified: "python doesn't support tail recursion." This string, however, is meme-ified: "PyThon dOeSn'T sUpPort TaIl reCuRsiOn." Write the function memeified below, which determines whether a string is meme-ified.

Q7: Greetings

Let's say hello to our fellow bears! We've received messages from our new friends at Berkeley, and we want to determine whether or not these messages are greetings. In this problem, there are two types of greetings - salutations and valedictions. The first are messages that start with "hi", "hello", or "hey", where the first letter of these words can be either capitalized or lowercase. The second are messages that end with the word "bye" (capitalized or lowercase), followed by either an exclamation point, a period, or no punctuation. Write a regular expression that determines whether a given message is a greeting.

Run in 61A CodeQ8: Email Domain Validator

Create a regular expression that makes sure a given string email is a valid email address and that its domain name is in the provided list of domains.

An email address is valid if it contains letters, number, or underscores, followed by an @ symbol, then a domain.

All domains will have a 3 letter extension following the period.

Hint: For this problem, you will have to make a regex pattern based on the inputs domains. A for loop can help with that.

Extra: There is a particularly elegant solution that utilizes join and replace

Note: The skeleton code is just a suggestion; feel free to use your own structure if you prefer.

Run in 61A CodeExam Prep

Questions

Q9: Insert

Write a tail-recursive function that inserts a number n into a non-empty

sorted list of numbers, s.

scm> (insert 1 '(2))

(1 2)

scm> (insert 5 '(2 4 6 8))

(2 4 5 6 8)

scm> (insert 1000 '(1 2 3 4 5 6))

(1 2 3 4 5 6 1000)Hint: Use the built-in Scheme function

appendto concatenate two lists together.

scm> (append '(1 2) '(3 4))

(1 2 3 4)

scm> (append '(2 4 6) '())

(2 4 6)

scm> (append '() '(5 3 1))

(5 3 1)Q10: Fast-Exp

We can write a faster version of exp , which is a function that raises a number b to the n-th power, that computes its answer much faster

using the method of repeated squaring:

(define (square x) (* x x))

(define (fast-exp-recursive b n)

(cond ((= n 0)

1)

((even? n)

(square (fast-exp-recursive b (/ n 2))))

(else

(* b (fast-exp-recursive b (- n 1))))))The previous exp procedure took a linear number of recursive calls,

because it always reduced n by 1. However, fast-exp halves the

value of n every two recursive calls at most, and so it takes a

logarithmic number of recursive calls. See SICP for more

details.

However, this new procedure is not tail recursive, and as a result can use up a lot of memory. In particular, the following will crash STk after a few seconds of computation:

(fast-exp-recursive 1 (- (fast-exp-recursive 2 20000) 1))Bonus question: Why did we subtract 1? In other words, why doesn't the following crash the interpreter?

(fast-exp-recursive 1 (fast-exp-recursive 2 20000))Back to the original question - write fast-exp using tail recursion

so that this no longer crashes. See SICP, Exercise 1.16, for a

hint.

Q11: Sp 17 Final: Pair Up

Fill in the Scheme pairs function so that (pairs L), where L is a list, produces a list of lists, where each of

these lists contains a pair of elements from L.

scm> (pairs ’(1 2 3 4))

((1 2) (3 4))

scm> (pairs ’(1 2 3 4 5)) ; Odd element at end put in singleton list.

((1 2) (3 4) (5))

scm> (pairs ’())

()The function must be tail-recursive. You need not define (or use) the reverse function.