Lab 5: Trees

Due at 11:59pm on Friday, 03/01/2019.

Starter Files

Download lab05.zip. Inside the archive, you will find starter files for the questions in this lab, along with a copy of the Ok autograder.

Submission

By the end of this lab, you should have submitted the lab with

python3 ok --submit. You may submit more than once before the

deadline; only the final submission will be graded.

Check that you have successfully submitted your code on

okpy.org.

Topics

Consult this section if you need a refresher on the material for this lab. It's okay to skip directly to the questions and refer back here should you get stuck.

Sequences

Sequences are ordered collections of values that support element-selection and have length. The most common sequences you've worked with are lists, but many other Python types are sequences as well, including strings.

For Statements

We've learned about one method of iteration already -- while statements, which repeats code based on a conditional expression. It is also possible to iterate through a sequence and repeat code for each element in the sequence. This is done with a for statement, which has the following syntax:

for <name> in <expression>:

<suite>First, <expression> is evaluated. It must evaluate to a sequence, or else an

error will be produced. Then, for each element in the sequence in order,

<name>is bound to its value.<suite>is executed.

Here is an example where <expression> is a list expression:

for x in [-1, 4, 2, 0, 5]:

print("Current elem:", x)This would output the following:

Current elem: -1

Current elem: 4

Current elem: 2

Current elem: 0

Current elem: 5Trees

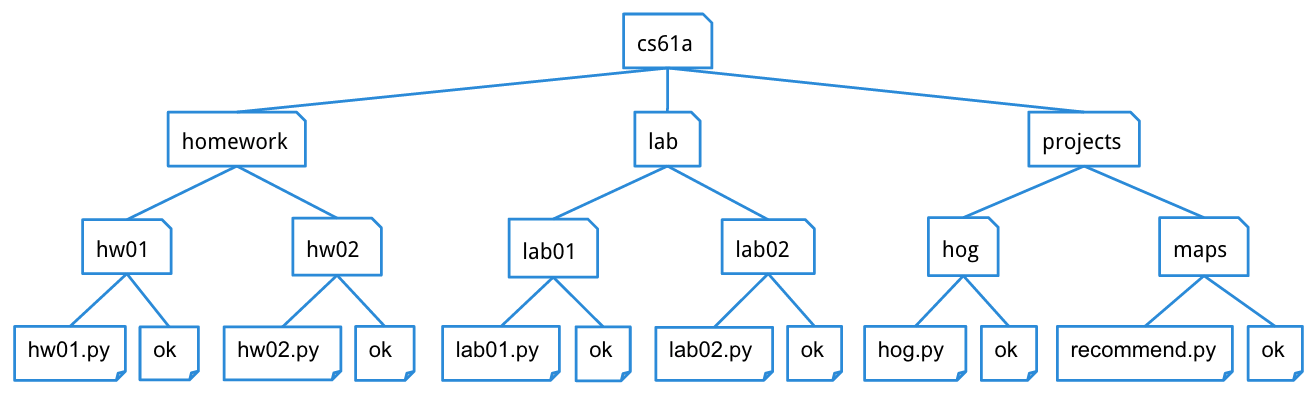

A tree is a data structure that represents a hierarchy of information. A file system is a good example of a tree structure. For example, within your cs61a folder, you have folders separating your projects, lab assignments, and homework. The next level is folders that separate different assignments, hw01, lab01, hog, etc., and inside those are the files themselves, including the starter files and ok. Below is an incomplete diagram of what your cs61a directory might look like.

As you can see, unlike trees in nature, the tree abstract data type is drawn with the root at the top and the leaves at the bottom.

Some tree terminology:

- root: the node at the top of the tree

- label: the value in a node, selected by the

labelfunction - branches: a list of trees directly under the tree's root, selected by the

branchesfunction - leaf: a tree with zero branches

- node: any location within the tree (e.g., root node, leaf nodes, etc.)

Our tree abstract data type consists of a root and a list of its

branches. To create a tree and access its root value and branches, use the

following constructor and selectors:

Constructor

tree(label, branches=[]): creates a tree object with the givenlabelvalue at its root node and list ofbranches. Notice that the second argument to this constructor,branches, is optional - if you want to make a tree with no branches, leave this argument empty.

Selectors

label(tree): returns the value in the root node oftree.branches(tree): returns the list of branches of the giventree.

Convenience function

is_leaf(tree): returnsTrueiftree's list ofbranchesis empty, andFalseotherwise.

For example, the tree generated by

number_tree = tree(1,

[tree(2),

tree(3,

[tree(4),

tree(5)]),

tree(6,

[tree(7)])])would look like this:

1

/ | \

2 3 6

/ \ \

4 5 7To extract the number 3 from this tree, which is the label of the root of its second branch, we would do this:

label(branches(number_tree)[1])The print_tree function prints out a tree in a

human-readable form. The exact form follows the pattern illustrated

above, where the root is unindented, and each of its branches is

indented one level further.

def print_tree(t, indent=0):

"""Print a representation of this tree in which each node is

indented by two spaces times its depth from the root.

>>> print_tree(tree(1))

1

>>> print_tree(tree(1, [tree(2)]))

1

2

>>> numbers = tree(1, [tree(2), tree(3, [tree(4), tree(5)]), tree(6, [tree(7)])])

>>> print_tree(numbers)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

"""

print(' ' * indent + str(label(t)))

for b in branches(t):

print_tree(b, indent + 1)Checkoff

Q1: Partition Options

Recall the count_partitions function from lecture:

>>> def count_partitions(total, biggest_num):

... if total == 0:

... return 1

... elif total < 0:

... return 0

... elif biggest_num == 0:

... return 0

... else:

... with_biggest = count_partitions(total - biggest_num, biggest_num)

... without_biggest = count_partitions(total, biggest_num - 1)

... return with_biggest + without_biggest

...If you don't understand what's going on, feel free to flag down an AI or TA to explain. Once you're confident that you understand, consider the following modification. partition_options returns all possible partitions of total using numbers no biggest than biggest_num. count_partitions returned the number of possible partitions, but here we are going to actually return all the possible unique sums that sum tot total.

Some examples:

>>> partition_options(2, 1)

[[1, 1]]

>>> partition_options(2, 2)

[[2], [1, 1]]

>>> partition_options(3, 3)

[[3], [2, 1], [1, 1, 1]]

>>> partition_options(4, 3)

[[3, 1], [2, 2], [2, 1, 1], [1, 1, 1, 1]]

>>> partition_options(6, 4)

[[4, 2], [4, 1, 1], [3, 3], [3, 2, 1], [3, 1, 1, 1], [2, 2, 2], [2, 2, 1, 1], [2, 1, 1, 1, 1], [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]]Now implement partition_options, using count_partitions as a reference. If you would like to be checked off, put yourself on the checkoff queue in lab.

>>> def partitions_options(total, biggest_num):

... if total == 0:

... return [[]]

... elif total < 0:

... return []

... elif biggest_num == 0:

... return []

... else:

... with_biggest = ____________

... without_biggest = ____________

... ___________ = [[________] _______ for elem in with_biggest] # what extra step do we need here?

... return with_biggest + without_biggest

...with_biggest and without_biggest are exactly the same as count_partitions. However, we need to add [biggest_num] to every elem in with_biggest. The reason for this is easiest to see by walking through the simple example of partition_options(2, 1). Hence, the blanks should be

with_biggest = partition_options(total-biggest_num, biggest_num)

without_biggest = partition_options(total, biggest_num-1)

with_biggest = [[biggest_num] + elem for elem in with_biggest]Required Questions

Q2: WWPD: Lists?

What would Python display? Try to figure it out before you type it into the interpreter!

Use Ok to test your knowledge with the following "What Would Python Display?" questions:

python3 ok -q lists -u

>>> [x*x for x in range(5)]

______[0, 1, 4, 9, 16]

>>> [n for n in range(10) if n % 2 == 0]

______[0, 2, 4, 6, 8]

>>> [i+5 for i in [n for n in range(1,4)]]

______[6, 7, 8]>>> [i**2 for i in range(10) if i < 3]

______[0, 1, 4]

>>> lst = ['hi' for i in [1, 2, 3]]

>>> print(lst)

______['hi', 'hi', 'hi']

>>> lst + [i for i in ['1', '2', '3']]

______['hi', 'hi', 'hi', '1', '2', '3']Q3: If This Not That

Define if_this_not_that, which takes a list of integers i_list and an

integer this. For each element in i_list, if the element is larger than

this, then print the element. Otherwise, print "that".

def if_this_not_that(i_list, this):

"""Define a function which takes a list of integers `i_list` and an integer

`this`. For each element in `i_list`, print the element if it is larger

than `this`; otherwise, print the word "that".

>>> original_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

>>> if_this_not_that(original_list, 3)

that

that

that

4

5

"""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

for elem in i_list:

if elem <= this:

print("that")

else:

print(elem)

# List comprehension version

def if_this_not_that(i_list, this):

[print(i) if i > this else print('that') for i in i_list]

Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q if_this_not_thatQ4: Acorn Finder

The squirrels on campus need your help! There are a lot of trees on campus and

the squirrels would like to know which ones contain acorns. Define the function

acorn_finder, which takes in a tree and returns True if the tree contains a

node with the value 'acorn' and False otherwise.

def acorn_finder(t):

"""Returns True if t contains a node with the value 'acorn' and

False otherwise.

>>> scrat = tree('acorn')

>>> acorn_finder(scrat)

True

>>> sproul = tree('roots', [tree('branch1', [tree('leaf'), tree('acorn')]), tree('branch2')])

>>> acorn_finder(sproul)

True

>>> numbers = tree(1, [tree(2), tree(3, [tree(4), tree(5)]), tree(6, [tree(7)])])

>>> acorn_finder(numbers)

False

>>> t = tree(1, [tree('acorn',[tree('not acorn')])])

>>> acorn_finder(t)

True

"""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

if label(t) == 'acorn':

return True

for b in branches(t):

if acorn_finder(b):

return True

return False

# Alternative solution

def acorn_finder(t):

if label(t) == 'acorn':

return True

return True in [acorn_finder(b) for b in branches(t)]Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q acorn_finderOptional Questions

Shakespeare and Dictionaries

We will use dictionaries to approximate the entire works of Shakespeare! We're going to use a bigram language model. Here's the idea: We start with some word -- we'll use "The" as an example. Then we look through all of the texts of Shakespeare and for every instance of "The" we record the word that follows "The" and add it to a list, known as the successors of "The". Now suppose we've done this for every word Shakespeare has used, ever.

Let's go back to "The". Now, we randomly choose a word from this list, say "cat". Then we look up the successors of "cat" and randomly choose a word from that list, and we continue this process. This eventually will terminate in a period (".") and we will have generated a Shakespearean sentence!

The object that we'll be looking things up in is called a "successor table", although really it's just a dictionary. The keys in this dictionary are words, and the values are lists of successors to those words.

Q5: Successor Tables

Here's an incomplete definition of thebuild_successors_table

function. The input is a list of words (corresponding to a

Shakespearean text), and the output is a successors table. (By default,

the first word is a successor to "."). See the example below.

Note: there are two places where you need to write code, denoted by the two

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

def build_successors_table(tokens):

"""Return a dictionary: keys are words; values are lists of successors.

>>> text = ['We', 'came', 'to', 'investigate', ',', 'catch', 'bad', 'guys', 'and', 'to', 'eat', 'pie', '.']

>>> table = build_successors_table(text)

>>> sorted(table)

[',', '.', 'We', 'and', 'bad', 'came', 'catch', 'eat', 'guys', 'investigate', 'pie', 'to']

>>> table['to']

['investigate', 'eat']

>>> table['pie']

['.']

>>> table['.']

['We']

"""

table = {}

prev = '.'

for word in tokens:

if prev not in table:

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

table[prev] = [] "*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

table[prev] += [word] prev = word

return tableUse Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q build_successors_tableQ6: Construct the Sentence

Let's generate some sentences! Suppose we're given a starting word. We can look up this word in our table to find its list of successors, and then randomly select a word from this list to be the next word in the sentence. Then we just repeat until we reach some ending punctuation.

Hint: to randomly select from a list, import the Python random library with

import randomand use the expressionrandom.choice(my_list)

This might not be a bad time to play around with adding strings

together as well. Let's fill in the construct_sent function!

def construct_sent(word, table):

"""Prints a random sentence starting with word, sampling from

table.

>>> table = {'Wow': ['!'], 'Sentences': ['are'], 'are': ['cool'], 'cool': ['.']}

>>> construct_sent('Wow', table)

'Wow!'

>>> construct_sent('Sentences', table)

'Sentences are cool.'

"""

import random

result = ''

while word not in ['.', '!', '?']:

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

result += word + ' '

word = random.choice(table[word]) return result.strip() + wordUse Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q construct_sentPutting it all together

Great! Now let's try to run our functions with some actual data. The following snippet included in the skeleton code will return a list containing the words in all of the works of Shakespeare.

Warning: Do NOT try to print the return result of this function.

def shakespeare_tokens(path='shakespeare.txt', url='http://composingprograms.com/shakespeare.txt'):

"""Return the words of Shakespeare's plays as a list."""

import os

from urllib.request import urlopen

if os.path.exists(path):

return open('shakespeare.txt', encoding='ascii').read().split()

else:

shakespeare = urlopen(url)

return shakespeare.read().decode(encoding='ascii').split()Uncomment the following two lines to run the above function and build the successors table from those tokens.

# Uncomment the following two lines

# tokens = shakespeare_tokens()

# table = build_successors_table(tokens)Next, let's define a utility function that constructs sentences from this successors table:

>>> def sent():

... return construct_sent('The', table)

>>> sent()

" The plebeians have done us must be news-cramm'd."

>>> sent()

" The ravish'd thee , with the mercy of beauty!"

>>> sent()

" The bird of Tunis , or two white and plucker down with better ; that's God's sake."Notice that all the sentences start with the word "The". With a few

modifications, we can make our sentences start with a random word. The

following random_sent function (defined in your starter file) will

do the trick:

def random_sent():

import random

return construct_sent(random.choice(table['.']), table)Go ahead and load your file into Python (be sure to use the -i flag).

You can now call the random_sent function to generate random

Shakespearean sentences!

>>> random_sent()

' Long live by thy name , then , Dost thou more angel , good Master Deep-vow , And tak'st more ado but following her , my sight Of speaking false!'

>>> random_sent()

' Yes , why blame him , as is as I shall find a case , That plays at the public weal or the ghost.'More Trees Practice

Q7: Sprout leaves

Define a function sprout_leaves that takes in a tree, t, and a list of

values, vals. It produces a new tree that is identical to t, but where each

old leaf node has new branches, one for each value in vals.

For example, say we have the tree t = tree(1, [tree(2), tree(3, [tree(4)])]):

1

/ \

2 3

|

4If we call sprout_leaves(t, [5, 6]), the result is the following tree:

1

/ \

2 3

/ \ |

5 6 4

/ \

5 6def sprout_leaves(t, vals):

"""Sprout new leaves containing the data in vals at each leaf in

the original tree t and return the resulting tree.

>>> t1 = tree(1, [tree(2), tree(3)])

>>> print_tree(t1)

1

2

3

>>> new1 = sprout_leaves(t1, [4, 5])

>>> print_tree(new1)

1

2

4

5

3

4

5

>>> t2 = tree(1, [tree(2, [tree(3)])])

>>> print_tree(t2)

1

2

3

>>> new2 = sprout_leaves(t2, [6, 1, 2])

>>> print_tree(new2)

1

2

3

6

1

2

"""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

if is_leaf(t):

return tree(label(t), [tree(v) for v in vals])

return tree(label(t), [sprout_leaves(s, vals) for s in branches(t)])Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q sprout_leavesQ8: Add trees

Define the function add_trees, which takes in two trees and returns a new

tree where each corresponding node from the first tree is added with the node

from the second tree. If a node at any particular position is present in one

tree but not the other, it should be present in the new tree as well.

Hint: You may want to use the built-in zip function to iterate over multiple sequences at once.

Note: If you feel that this one's a lot harder than the previous tree problems, that's totally fine! This is a pretty difficult problem, but you can do it! Talk about it with other students, and come back to it if you need to.

def add_trees(t1, t2):

"""

>>> numbers = tree(1,

... [tree(2,

... [tree(3),

... tree(4)]),

... tree(5,

... [tree(6,

... [tree(7)]),

... tree(8)])])

>>> print_tree(add_trees(numbers, numbers))

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

>>> print_tree(add_trees(tree(2), tree(3, [tree(4), tree(5)])))

5

4

5

>>> print_tree(add_trees(tree(2, [tree(3)]), tree(2, [tree(3), tree(4)])))

4

6

4

>>> print_tree(add_trees(tree(2, [tree(3, [tree(4), tree(5)])]), \

tree(2, [tree(3, [tree(4)]), tree(5)])))

4

6

8

5

5

"""

"*** YOUR CODE HERE ***"

if not t1:

return t2

if not t2:

return t1

new_label = label(t1) + label(t2)

t1_children, t2_children = branches(t1), branches(t2)

length_t1, length_t2 = len(t1_children), len(t2_children)

if length_t1 < length_t2:

t1_children += [None for _ in range(length_t1, length_t2)]

elif len(t1_children) > len(t2_children):

t2_children += [None for _ in range(length_t2, length_t1)]

return tree(new_label, [add_trees(child1, child2) for child1, child2 in zip(t1_children, t2_children)])Use Ok to test your code:

python3 ok -q add_trees