Internal Structures

Real Git distinguishes several different kinds of objects. For our purposes, the important ones are

- blobs: Essentially the contents of files.

- trees: Directory structures mapping names to references to blobs and other trees (subdirectories).

- commits: Combinations of log messages,

other metadata (commit date, author,

etc.), a reference to a tree, and references to

parent commits.

The repository also maintains a mapping from branch heads (in this course,

we've used names

like

master,proj2, etc.) to references to commits, so that certain important commits have symbolic names.

We will simplify from Git still further by

- Incorporating trees into commits and not dealing with subdirectories (so there will be one "flat" directory of plain files for each repository).

- Limiting ourselves to merges that reference two parents (in real Git, there can be any number of parents.)

- Having our metadata consist only of a timestamp and log message. A commit, therefore, will consist of a log message, timestamp, a mapping of file names to blob references, a parent reference, and (for merges) a second parent reference.

Every object—every blob and every commit in our case—has a unique integer id that serves as a reference to the object. An interesting feature of Git is that these ids are universal: unlike a typical Java implementation, two objects with exactly the same content will have the same id on all systems (i.e. my computer, your computer, and anyone else's computer will compute this same exact id). In the case of blobs, "same content" means the same file contents. In the case of commits, it means the same metadata, the same mapping of names to references, and the same parent reference. The objects in a repository are thus said to be content addressable.

Both Git and Gitlet accomplish this the same way: by using a cryptographic hash function called SHA-1 (Secure Hash 1), which produces a 160-bit integer hash from any sequence of bytes. Cryptographic hash functions have the property that it is extremely difficult to find two different byte streams with the same hash value (or indeed to find any byte stream given just its hash value), so that essentially, we may assume that the probability that any two objects with different contents have the same SHA-1 hash value is 2-160 or about 10-48. Basically, we simply ignore the possibility of a hashing collision, so that the system has, in principle, a fundamental bug that in practice never occurs!

Fortunately, there are library classes for computing SHA-1 values, so you won't have to deal with the actual algorithm. All you have to do is to make sure that you correctly label all your objects. In particular, this involves

- Including all metadata and references when hashing a commit.

- Distinguishing somehow between hashes for commits and hashes for blobs. A

good way of doing this involves a well-thought out directory structure

within the

.gitletdirectory. Another way to do so is to hash in an extra word for each object that has one value for blobs and another for commits.

By the way, the SHA-1 hash value, rendered as a 40-character

hexadecimal string, makes

a convenient file name for storing your data in your .gitlet

directory (more on that below). It also gives you a convenient way to

compare two files (blobs) to see if they have the same contents: if their

SHA-1s are the same, we simply assume the files are the same.

For remotes (like origin and shared, which we've been using all semester),

we'll simply use other Gitlet repositories. Pushing simply means copying all

commits and blobs that the remote repository does not yet have to the remote

repository, and resetting a branch reference. Pulling is the same, but in the

other direction. Remotes are extra credit in this project and not required for

full credit.

Reading and writing your internal objects from and to files is actually pretty

easy, thanks to Java's serialization facilities. The interface

java.io.Serializable has no methods,

but if a class implements it, then the Java

runtime will automatically provide a way to convert to and from a stream of

bytes, which you can then write to a file using the I/O class

java.io.ObjectOutputStream and read back (and deserialize) with

java.io.ObjectInputStream.

The term "serialization" refers to the conversion from some arbitrary structure

(array, tree, graph, etc.) to a serial sequence of bytes. You should have seen

and gotten practice with serialization in lab 11. You'll be using a very similar

approach here, so do use your lab11 as a resource when it comes to persistence

and serialization.

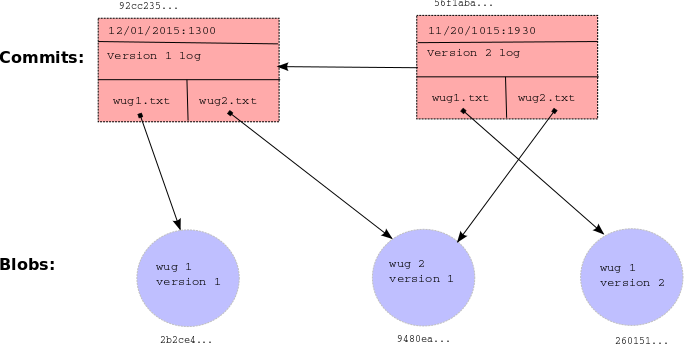

Here is a summary example of the structures discussed in this section.

As you can see, each commit (rectangle) points to some blobs (circles), which

contain file contents. The commits contain the file names and references to

these blobs, as well as a parent link. These references, depicted as arrows,

are represented in the .gitlet directory using their SHA-1 hash values (the

small hexadecimal numerals above the commits and below the blobs). The newer

commit contains an updated version of wug1.txt, but shares the same version

of wug2.txt as the older commit. Your commit class will somehow store all of

the information that this diagram shows: a careful selection of internal data

structures will make the implementation easier or harder, so it behooves you to

spend time planning and thinking about the best way to store everything.