Overview of Gitlet

In this project you'll be implementing a version-control system that mimics some of the basic features of the popular system Git. Ours is smaller and simpler, however, so we have named it Gitlet.

A version-control system is essentially a backup system for related collections of files. The main functionality that Gitlet supports is:

- Saving the contents of entire directories of files. In Gitlet, this is called committing, and the saved contents themselves are called commits.

- Restoring a version of one or more files or entire commits. In Gitlet, this is called checking out those files or that commit.

- Viewing the history of your backups. In Gitlet, you view this history in something called the log.

- Maintaining related sequences of commits, called branches.

- Merging changes made in one branch into another.

The point of a version-control system is to help you when creating complicated (or even not-so-complicated) projects, or when collaborating with others on a project. You save versions of the project periodically. If at some later point in time you accidentally mess up your code, then you can restore your source to a previously committed version (without losing any of the changes you made since then). If your collaborators make changes embodied in a commit, you can incorporate (merge) these changes into your own version.

In Gitlet, you don't just commit individual files at a time. Instead, you can commit a coherent set of files at the same time. We like to think of each commit as a snapshot of your entire project at one point in time. However, for simplicity, many of the examples in the remainder of this document involve changes to just one file at a time. Just keep in mind you could change multiple files in each commit.

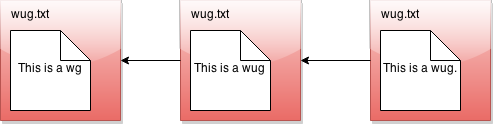

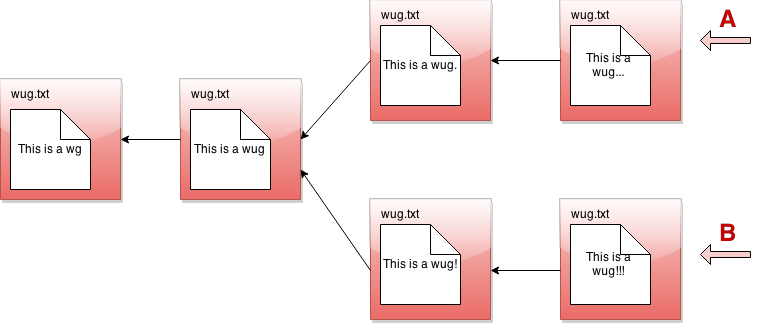

In this project, it will be helpful for us to visualize the commits we

make over time. Suppose we have a project consisting just of the

file wug.txt, we add some text to

it, and commit it. Then we modify the file and commit these changes.

Then we modify the file again, and commit the changes again. Now we

have saved three total versions of this file, each one later

in time than the previous. We can visualize these commits like so:

Here we've drawn an arrow indicating that each commit contains some kind of reference to the commit that came before it. We call the commit that came before it the parent commit—this will be important later. But for now, does this drawing look familiar? That's right; it's a linked list!

The big idea behind Gitlet is that we can visualize the history of the different versions of our files in a list like this. Then it's easy for us to restore old versions of files. You can imagine making a command like: "Gitlet, please revert to the state of the files at commit #2", and it would go to the second node in the linked list and restore the copies of files found there, while removing any files that are in the first node, but not the second.

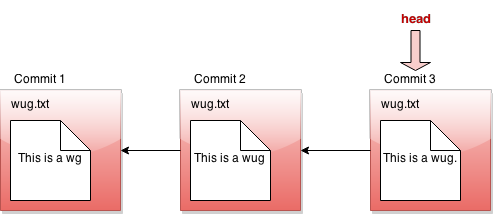

If we tell Gitlet to revert to an old commit, the front of the linked list will no longer reflect the current state of your files, which might be a little misleading. In order to fix this problem, we introduce something called the head pointer. The head pointer keeps track of where in the linked list we currently are. Normally, as we make commits, the head pointer will stay at the front of the linked list, indicating that the latest commit reflects the current state of the files:

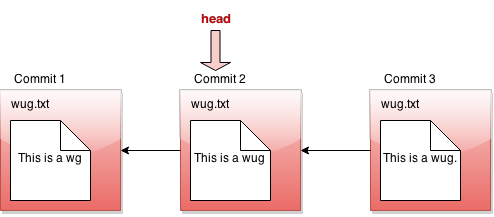

However, let's say we revert to the state of the files at commit #2 (technically, this is the reset command, which you'll see later in the spec). We move the head pointer back to show this:

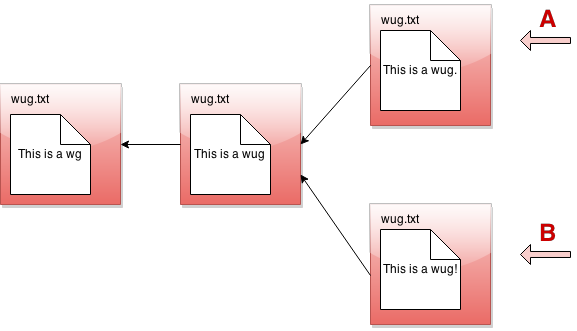

All right, now, if this were all Gitlet could do, it would be a pretty simple system. But Gitlet has one more trick up its sleeve: it doesn't just maintain older and newer versions of files, it can maintain differing versions. Imagine you're coding a project, and you have two ideas about how to proceed: let's call one Plan A, and the other Plan B. Gitlet allows you to save both versions, and switch between them at will. Here's what this might look like, in our pictures:

It's not really a linked list anymore. It's more like a tree. We'll call this thing the commit tree. Keeping with this metaphor, each of the separate versions is called a branch of the tree. You can develop each version separately:

There are two pointers into the tree, representing the furthest point of each branch. At any given time, only one of these is the currently active pointer, and this is what's called the head pointer. The head pointer is the pointer at the front of the current branch.

That's it for our brief overview of the Gitlet system! Don't worry if you don't fully understand it yet; the section above was just to give you a high level picture of what its meant to do. A detailed spec of what you're supposed to do for this project follows this section.

But a last word here: commit trees are immutable: once a commit node has been created, it can never be destroyed (or changed at all). We can only add new things to the commit tree, not modify existing things. This is an important feature of Gitlet! One of Gitlet's goals is to allow us to save things that we worked on in the past so we don't delete them accidentally; this functionality would be jeopardized if we were allowed to edit past commits.