6.5 D-Separation

One useful question to ask about a set of random variables is whether or not one variable is independent from another, or if one random variable is conditionally independent of another given a third random variable. Bayes’ Nets representation of joint probability distributions gives us a way to quickly answer such questions by inspecting the topological structure of the graph.

We already mentioned that a node is conditionally independent of all its ancestor nodes in the graph given all of its parents.

We will present all three canonical cases of connected three-node two-edge Bayes’ Nets, or triples, and the conditional independence relationships they express.

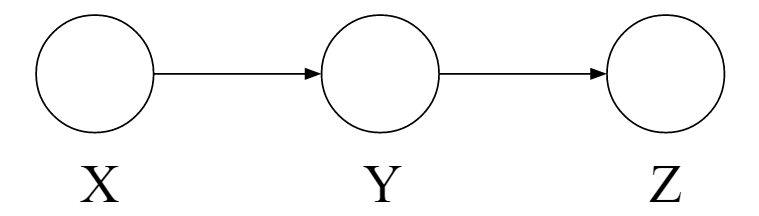

6.5.1 Causal Chains

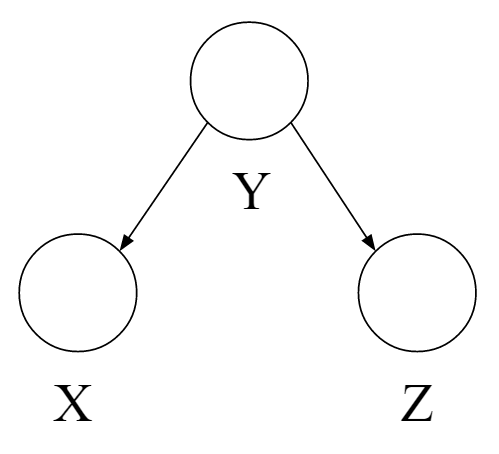

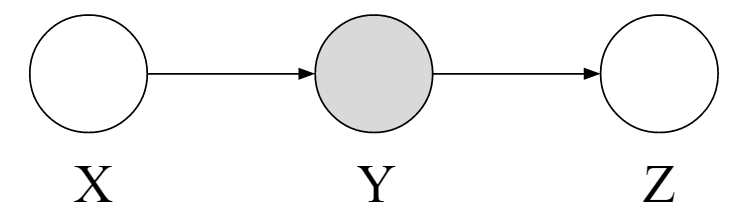

Figure 1 is a configuration of three nodes known as a causal chain. It expresses the following representation of the joint distribution over \(X\), \(Y\), and \(Z\):

\[P(x, y, z) = P(z|y)P(y|x)P(x)\]It’s important to note that \(X\) and \(Z\) are not guaranteed to be independent, as shown by the following counterexample:

\[P(y|x) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } x = y \\ 0 & \text{else } \end{cases}\] \[P(z|y) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } z = y \\ 0 & \text{else } \end{cases}\]

In this case, \(P(z|x) = 1\) if \(x = z\) and \(0\) otherwise, so \(X\) and \(Z\) are not independent.

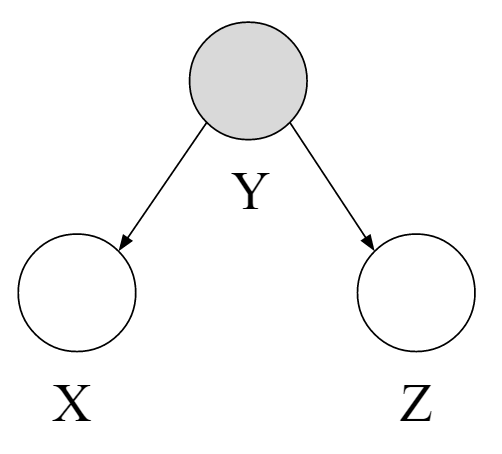

However, we can make the statement that \(X \perp\!\!\!\perp Z | Y\), as in Figure 2. Recall that this conditional independence means:

\[P(X | Z, Y) = P(X | Y)\]

We can prove this statement as follows:

\[P(X | Z, y) = \frac{P(X, Z, y)}{P(Z, y)} = \frac{P(Z|y) P(y|X) P(X)}{\sum_{x} P(x, y, Z)} = \frac{P(Z|y) P(y|X) P(X)}{P(Z|y) \sum_{x} P(y|x)P(x)} = \frac{P(y|X) P(X)}{\sum_{x} P(y|x)P(x)} = P(X|y)\]

An analogous proof can be used to show the same thing for the case where \(X\) has multiple parents. To summarize, in the causal chain configuration, \(X \perp\!\!\!\perp Z | Y\).

6.5.2 Common Cause

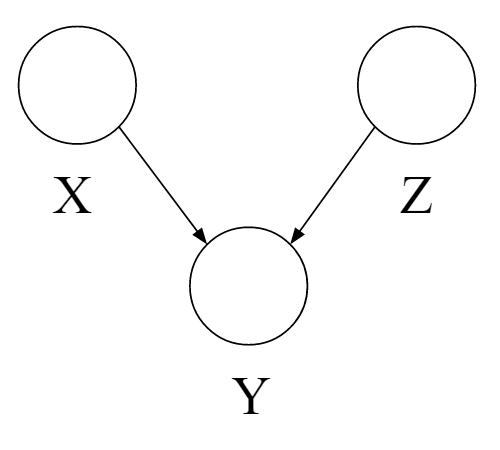

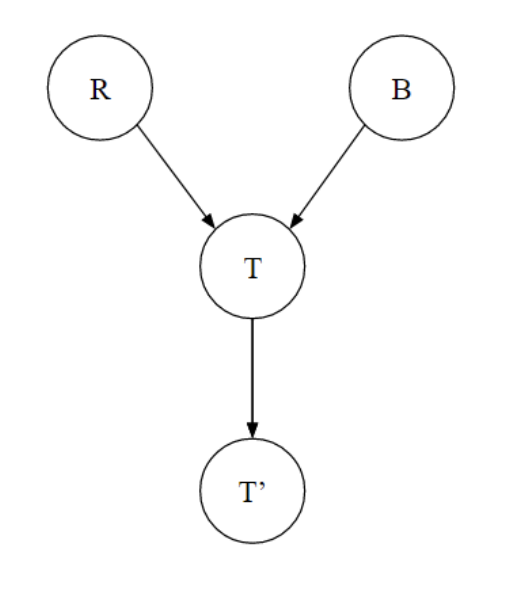

Figure 3: Common Cause with no observations.

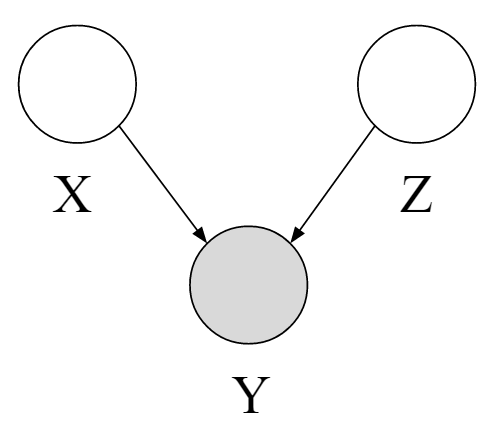

Figure 4: Common Cause with Y observed.

Another possible configuration for a triple is the common cause. It expresses the following representation:

\[P(x, y, z) = P(x|y)P(z|y)P(y)\]Just like with the causal chain, we can show that \(X\) is not guaranteed to be independent of \(Z\) with the following counterexample distribution:

\[P(x|y) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } x = y \\ 0 & \text{else } \end{cases}\] \[P(z|y) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } z = y \\ 0 & \text{else } \end{cases}\]

Then \(P(x|z) = 1\) if \(x = z\) and \(0\) otherwise, so \(X\) and \(Z\) are not independent.

But it is true that \(X \perp\!\!\!\perp Z | Y\). That is, \(X\) and \(Z\) are independent if \(Y\) is observed as in Figure 4. We can show this as follows:

\[P(X | Z, y) = \frac{P(X, Z, y)}{P(Z, y)} = \frac{P(X|y) P(Z|y) P(y)}{P(Z|y) P(y)} = P(X|y)\]6.5.3 Common Effect

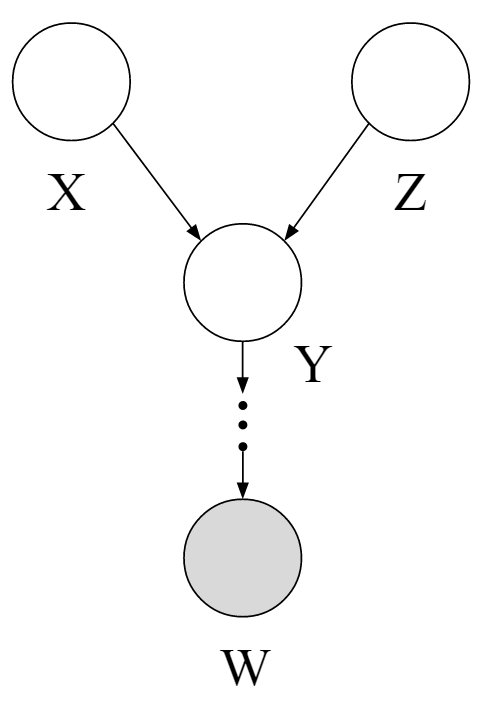

Figure 5: Common Effect with no observations.

Figure 6: Common Effect with Y observed.

It expresses the representation:

\[P(x, y, z) = P(y|x,z)P(x)P(z)\]In the configuration shown in Figure 5, \(X\) and \(Z\) are independent: \(X \perp\!\!\!\perp Z\). However, they are not necessarily independent when conditioned on \(Y\) (Figure 6). As an example, suppose all three are binary variables. \(X\) and \(Z\) are true and false with equal probability:

\[P(X=true) = P(X=false) = 0.5\] \[P(Z=true) = P(Z=false) = 0.5\]and \(Y\) is determined by whether \(X\) and \(Z\) have the same value:

\[P(Y | X, Z) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } X = Z \text{ and } Y = true \\ 1 & \text{if } X \ne Z \text{ and } Y = false \\ 0 & \text{else} \end{cases}\]Then \(X\) and \(Z\) are independent if \(Y\) is unobserved. But if \(Y\) is observed, then knowing \(X\) will tell us the value of \(Z\), and vice-versa. So \(X\) and \(Z\) are not conditionally independent given \(Y\).

Common Effect can be viewed as ``opposite’’ to Causal Chains and Common Cause — \(X\) and \(Z\) are guaranteed to be independent if \(Y\) is not conditioned on. But when conditioned on \(Y\), \(X\) and \(Z\) may be dependent depending on the specific probability values for \(P(Y | X, Z)\).

This same logic applies when conditioning on descendants of \(Y\) in the graph. If one of \(Y\)’s descendant nodes is observed, as in Figure 7, \(X\) and \(Z\) are not guaranteed to be independent.

Figure 7: Common Effect with child observations.

6.5.4 General Case, and D-separation

We can use the previous three cases as building blocks to help us answer conditional independence questions on an arbitrary Bayes’ Net with more than three nodes and two edges. We formulate the problem as follows:

Given a Bayes Net \(G\), two nodes \(X\) and \(Y\), and a (possibly empty) set of nodes \(\{Z_1, \dots Z_k\}\) that represent observed variables, must the following statement be true: \(X \perp\!\!\!\perp Y | \{Z_1, \dots Z_k\}\)?

D-separation (directed separation) is a property of the structure of the Bayes Net graph that implies this conditional independence relationship, and generalizes the cases we’ve seen above. If a set of variables \(Z_1, \cdots Z_k\) d-separates \(X\) and \(Y\), then \(X \perp\!\!\!\perp Y | \{Z_1, \cdots Z_k\}\) in all possible distributions that can be encoded by the Bayes net.

We start with an algorithm that is based on a notion of reachability from node \(X\) to node \(Y\). (Note: this algorithm is not quite correct! We’ll see how to fix it in a moment.)

- Shade all observed nodes \(\{Z_1, \dots Z_k\}\) in the graph.

- If there exists an undirected path from \(X\) and \(Y\) that is not blocked by a shaded node, \(X\) and \(Y\) are “connected”.

- If \(X\) and \(Y\) are connected, they’re not conditionally independent given \(\{Z_1, \dots Z_k\}\). Otherwise, they are.

However, this algorithm only works if the Bayes’ Net has no Common Effect structure within the graph, because if it exists, then two nodes are “reachable” when the \(Y\) node in Common Effect is activated (observed). To adjust for this, we arrive at the following d-separation algorithm:

- Shade all observed nodes \(\{Z_1, \dots Z_k\}\) in the graph.

- Enumerate all undirected paths from \(X\) to \(Y\).

- For each path:

- Decompose the path into triples (segments of 3 nodes).

- If all triples are active, this path is active and d-connects \(X\) to \(Y\).

-

If no path d-connects \(X\) and \(Y\), then \(X \perp\!\!\!\perp Y | \{Z_1, \dots Z_k\}\).

Any path in a graph from \(X\) to \(Y\) can be decomposed into a set of 3 consecutive nodes and 2 edges - each of which is called a triple. A triple is active or inactive depending on whether or not the middle node is observed. If all triples in a path are active, then the path is active and d-connects \(X\) to \(Y\), meaning \(X\) is not guaranteed to be conditionally independent of \(Y\) given the observed nodes. If all paths from \(X\) to \(Y\) are inactive, then \(X\) and \(Y\) are conditionally independent given the observed nodes.

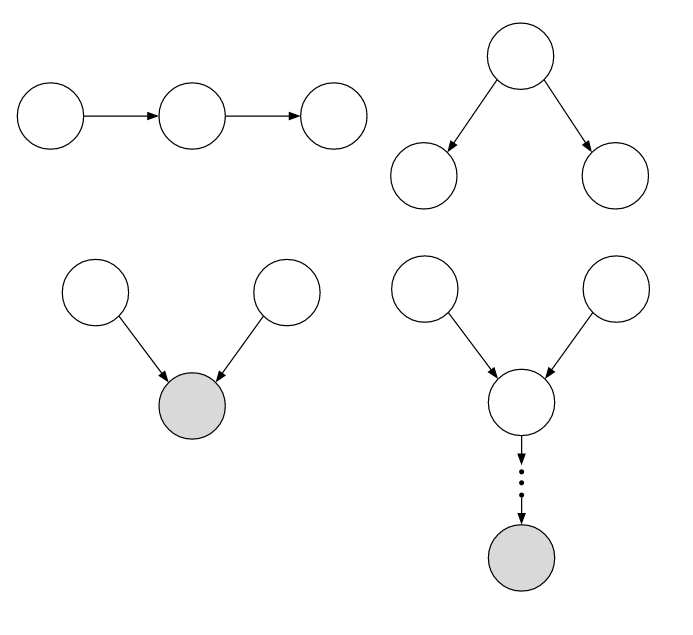

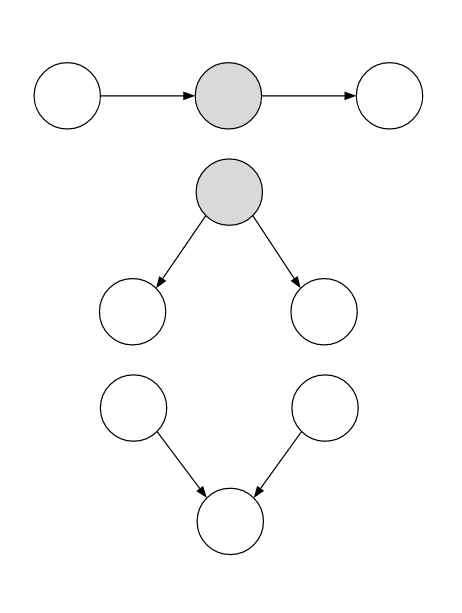

We can enumerate all possibilities of active and inactive triples using the three canonical graphs we presented below in the figures.

Active triples:

Inactive triples:

6.5.5 Examples

Here are some examples of applying the \(d\)-separation algorithm:

This graph contains the common effect and causal chain canonical graphs.

\(R \perp\!\!\!\perp B\) – Guaranteed

\(R \perp\!\!\!\perp B | T\) – Not guaranteed

\(R \perp\!\!\!\perp B | T'\) – Not guaranteed

\(R \perp\!\!\!\perp T' | T\) – Guaranteed

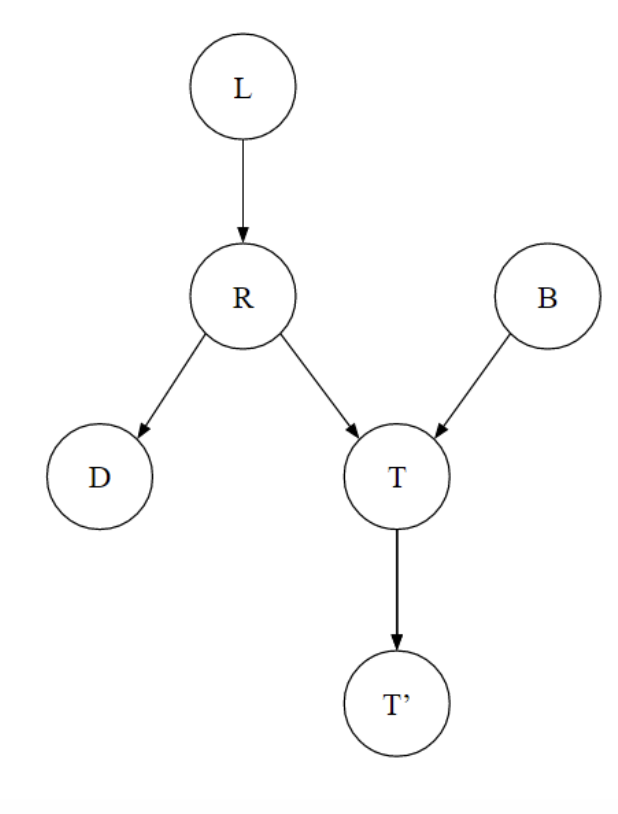

This graph contains combinations of all three canonical graphs (can you list them all?).

\(L \perp\!\!\!\perp T' | T\) – Guaranteed

\(L \perp\!\!\!\perp B\) – Guaranteed

\(L \perp\!\!\!\perp B | T\) – Not guaranteed

\(L \perp\!\!\!\perp B | T'\) – Not guaranteed

\(L \perp\!\!\!\perp B | T, R\) – Guaranteed

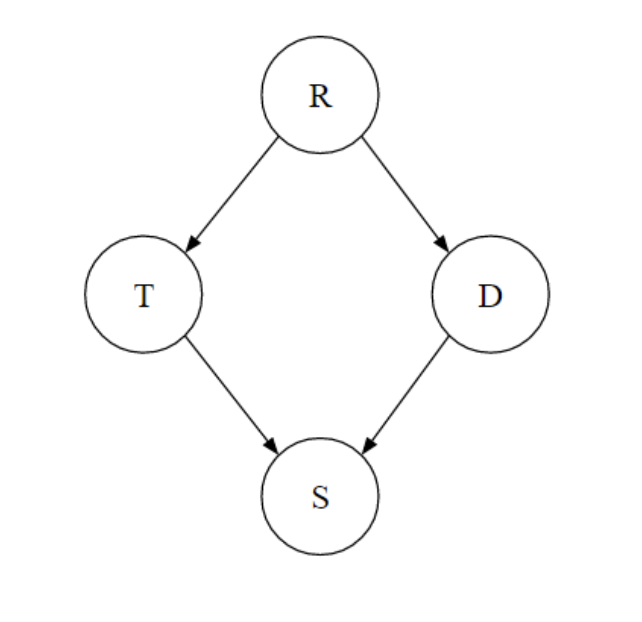

This graph contains combinations of all three canonical graphs.

\(T \perp\!\!\!\perp D\) – Not guaranteed

\(T \perp\!\!\!\perp D | R\) – Guaranteed

\(T \perp\!\!\!\perp D | R, S\) – Not guaranteed