10.5 Theorem Proving

An alternate approach is to apply rules of inference to \(KB\) to prove that \(KB \models q\). For example, if our knowledge base contains \(A\) and \(A \Rightarrow B\) then we can infer \(B\) (this rule is known as Modus Ponens). The two previously mentioned algorithms use the fact ii.) by writing \(A \wedge \neg B\) in CNF and show that it is either satisfiable or not.

We could also prove entailment using three rules of inference:

- If our knowledge base contains \(A\) and \(A \Rightarrow B\) we can infer \(B\) (Modus Ponens).

- If our knowledge base contains \(A \wedge B\) we can infer \(A\). We can also infer B. (And-Elimination).

- If our knowledge base contains \(A\) and \(B\) we can infer \(A \wedge B\) (Resolution).

The last rule forms the basis of the resolution algorithm, which iteratively applies it to the knowledge base and to the newly inferred sentences until either \(q\) is inferred, in which case we have shown that \(KB \models q\), or there is nothing left to infer, in which case \(KB \not\models q\).

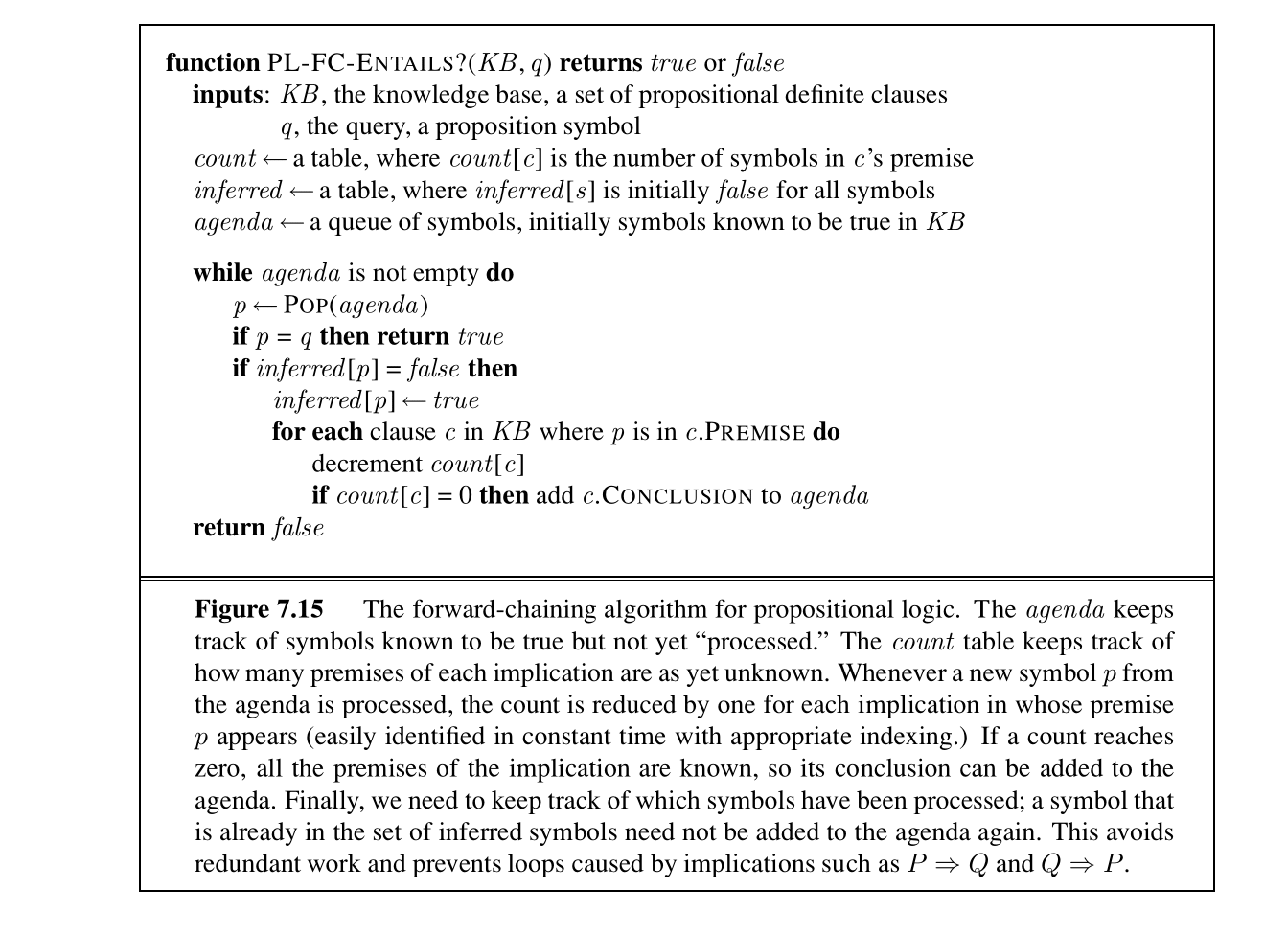

However, in the special case that our knowledge base only has literals (symbols by themselves) and implications: \((P_1 \wedge \cdots \wedge P_n \Rightarrow Q) \equiv (\neg P_1 \vee \cdots \vee \neg P_2 \vee Q)\), we can prove entailment in time linear to the size of the knowledge base. One algorithm, \(\textbf{forward chaining}\) iterates through every implication statement in which the \(\textbf{premise}\) (left hand side) is known to be true, adding the \(\textbf{conclusion}\) (right hand side) to the list of known facts. This is repeated until \(q\) is added to the list of known facts, or nothing more can be inferred.