10.4 Propositional Logical Inference

Logic is useful and powerful because it grants the ability to draw new conclusions from what we already know. To define the problem of inference we first need to define some terminology.

We say that a sentence \(A\) entails another sentence \(B\) if in all models that \(A\) is true, \(B\) is as well, and we represent this relationship as \(A \models B\). Note that if \(A \models B\) then the models of \(A\) are a subset of the models of \(B\), (\(M(A)\subseteq M(B)\)). The inference problem can be formulated as figuring out whether \(KB \models q\), where \(KB\) is our knowledge base of logical sentences, and \(q\) is some query. For example, if Elicia has avowed to never set foot in Crossroads again, we could infer that we will not find her when looking for friends to sit with for dinner.

We draw on two useful theorems to show entailment:

-

\(A \models B\) iff \(A \Rightarrow B\) is valid.

Proving entailment by showing that \(A \Rightarrow B\) is valid is known as a direct proof.

-

\(A \models B\) iff \(A \wedge \neg B\) is unsatisfiable.

Proving entailment by showing that \(A \wedge \neg B\) is unsatisfiable is known as a proof by contradiction.

10.4.1 Model Checking

One simple algorithm for checking whether \(KB \models q\) is to enumerate all possible models, and to check if in all the ones in which \(KB\) is true, \(q\) is true as well. This approach is known as model checking. In a sentence with a feasible number of symbols, enumeration can be done by drawing out a truth table.

For a propositional logical system, if there are \(N\) symbols, there are \(2^N\) models to check, and hence the time complexity of this algorithm is \(O(2^N)\), while in first-order logic, the number of models is infinite. In fact, the problem of propositional entailment is known to be co-NP-complete. While the worst-case runtime will inevitably be an exponential function of the size of the problem, there are algorithms that can in practice terminate much more quickly. We will discuss two model checking algorithms for propositional logic.

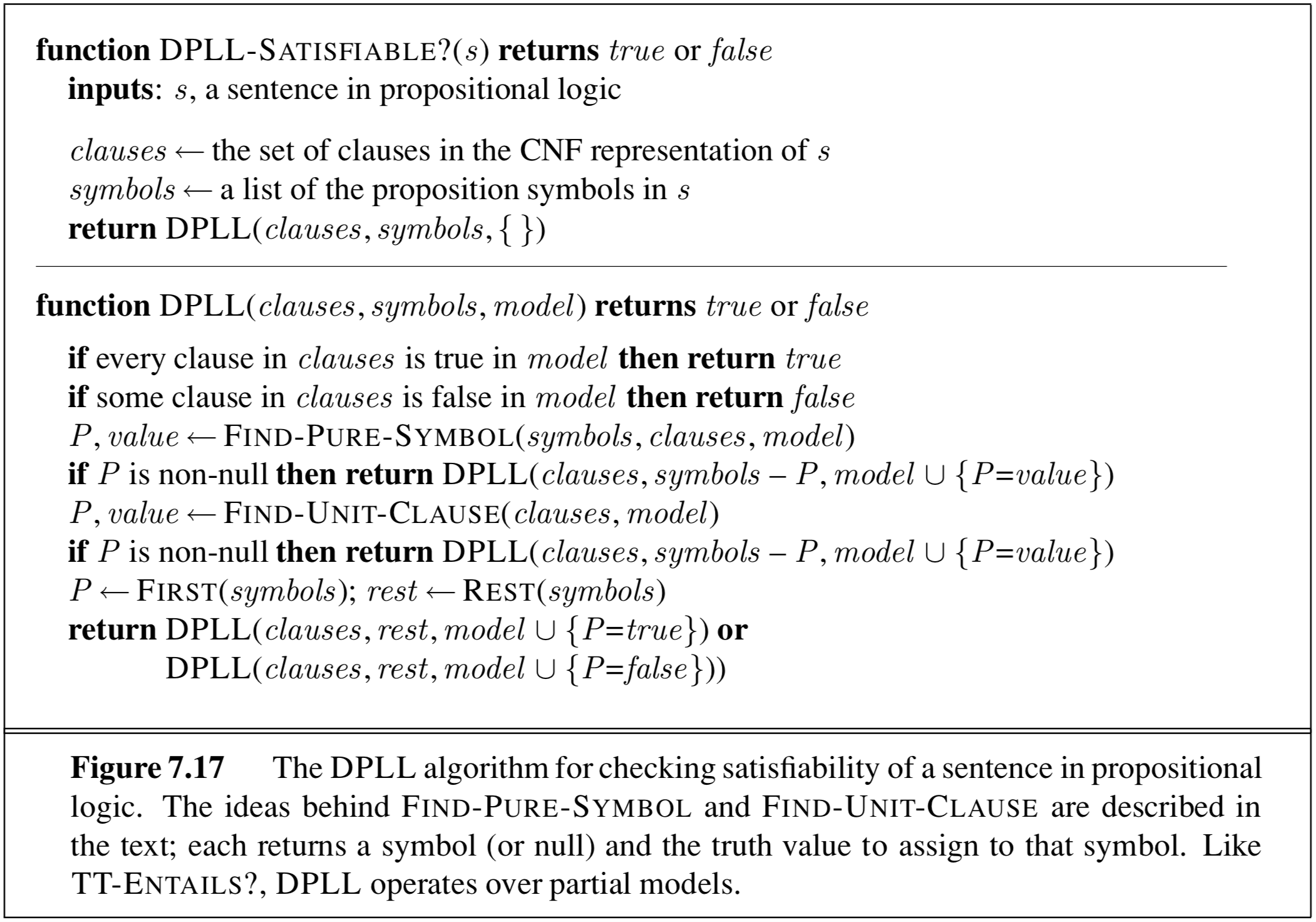

The first, proposed by Davis, Putnam, Logemann, and Loveland (which we will call the DPLL algorithm) is essentially a depth-first, backtracking search over possible models with three tricks to reduce excessive backtracking. This algorithm aims to solve the satisfiability problem, i.e. given a sentence, find a working assignment to all the symbols. As we mentioned, the problem of entailment can be reduced to one of satisfiability (show that \(A \wedge \neg B\) is not satisfiable), and specifically DPLL takes in a problem in CNF. Satisfiability can be formulated as a constraint satisfaction problem as follows: let the variables (nodes) be the symbols and the constraints be the logical constraints imposed by the CNF. Then DPLL will continue assigning symbols truth values until either a satisfying model is found or a symbol cannot be assigned without violating a logical constraint, at which point the algorithm will backtrack to the last working assignment. However, DPLL makes three improvements over simple backtracking search:

- Early Termination: A clause is true if any of the symbols are true. Therefore the sentence could be known to be true even before all symbols are assigned. Also, a sentence is false if any single clause is false. Early checking of whether the whole sentence can be judged true or false before all variables are assigned can prevent unnecessary meandering down subtrees.

- Pure Symbol Heuristic: A pure symbol is a symbol that only shows up in its positive form (or only in its negative form) throughout the entire sentence. Pure symbols can immediately be assigned true or false. For example, in the sentence \((A \vee B) \wedge (\neg B \vee C) \wedge (\neg C \vee A)\), we can identify \(A\) as the only pure symbol and can immediately A assign to true, reducing the satisfying problem to one of just finding a satisfying assignment of \((\neg B \vee C)\).

- Unit Clause Heuristic: A unit clause is a clause with just one literal or a disjunction with one literal and many falses. In a unit clause, we can immediately assign a value to the literal since there is only one valid assignment. For example, \(B\) must be true for the unit clause \((B \vee false \vee \cdots \vee false)\) to be true.

10.4.2 DPLL: Example

Suppose we have the

following sentence in conjunctive normal form (CNF):

\[(\neg N \vee \neg S) \land (M \vee Q \vee N) \land (L \vee \neg M) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P \vee N) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L) \land (S)\]We want to use the DPLL algorithm to determine whether it is satisfiable. Suppose we use a fixed variable ordering (alphabetical order) and a fixed value ordering (true before false).

On each recursive call to the DPLL function, we keep track of three things:

- model is a list of the symbols we’ve assigned so far, and their values.

- symbols is a list of unassigned symbols that still need assignments.

- clauses is a list of clauses (disjunctions) in CNF that still need to be considered on this call or future recursive calls to DPLL.

We start by calling DPLL with an empty model (no symbols assigned yet), symbols containing all the symbols in the original sentence, and clauses containing all the clauses in the original sentence.

Our initial DPLL call looks like this:

- model: \(\{\}\)

- symbols: \([L, M, N, P, Q, R, S]\)

- clauses: \((\neg N \vee \neg S) \land (M \vee Q \vee N) \land (L \vee \neg M) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P \vee N) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L) \land (S)\)

First, we apply early termination: we check if given the current model, every clause is true, or at least one clause is false. Since the model hasn’t assigned any symbol yet, we don’t know which clauses are true or false yet.

Next, we check for pure literals. There are no symbols that only appear in a non-negated form, or symbols that only appear in a negated form, so there are no pure literals that we can simplify. For example, \(N\) is not a pure literal because the first clause uses the negated \(\neg N\), and the second clause uses the non-negated \(N\).

Next, we check for unit clauses (clauses with just one symbol). There’s one unit clause \(S\). For this overall sentence to be true, we know that \(S\) has to be true (there’s no other way to satisfy that clause). Therefore, we can make another call to DPLL with \(S\) assigned to true in our model, and \(S\) removed from the list of symbols that still need assignments.

Our second DPLL call looks like this:

- model: \(\{ {\color{red} S: T} \}\)

- symbols: \([L, M, N, P, Q, R]\)

- clauses: \((\neg N \vee \neg S) \land (M \vee Q \vee N) \land (L \vee \neg M) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P \vee N) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L) \land (S)\)

First, we can simplify the clauses by substituting in the new assignment (\(S\) is true, and \(\neg S\) is false) from our model:

\[(\neg N \vee {\color{red} F}) \land (M \vee Q \vee N) \land (L \vee \neg M) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P \vee N) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L) \land ({\color{red} T})\] \[(\neg N) \land (M \vee Q \vee N) \land (L \vee \neg M) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P \vee N) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\]With our new simplified clauses, we can check for early termination. We still don’t have enough information to conclude that all sentences are true, or at least one sentence is false.

Next, we check for pure literals. As before, there are no symbols that only appear in a non-negated form, or symbols that appear in a negated form.

Next, we check for unit clauses. There’s one unit clause \((\neg N)\). For this overall sentence to be true, \((\neg N)\) must be true, so \(N\) must be false.

Therefore, we can make another call to DPLL with \(N\) assigned to false in our model, and \(N\) removed from the list of symbols that still need assignments. We can also use the simplified clause that we computed from this call in DPLL (where we simplified \(S\) out of the clauses).

Our third DPLL call looks like this:

- model: \(\{S:T, {\color{red} N:F}\}\)

- symbols: \([L, M, P, Q, R]\)

- clauses: \((\neg N) \land (M \vee Q \vee N) \land (L \vee \neg M) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P \vee N) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\)

The first thing we do on this call is simplifying clauses by substituting in the new assignment (\(N\) is false, and \(\neg N\) is true) from our model:

\[({\color{red} T}) \land (M \vee Q \vee {\color{red} F}) \land (L \vee \neg M) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P \vee {\color{red} F}) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\] \[(M \vee Q) \land (L \vee \neg M) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\]With our new simplified clause, we check for early termination, and then we check for pure literals. As before, we don’t find either one.

Next, we check for unit clauses. We don’t find any clauses with just one symbol left.

At this point, we need to try to assign a value to a variable. From our fixed variable ordering, we’ll assign \(M\) first, and from our fixed value ordering, we’ll try making \(M\) true first. If assigning \(M\) true leads to an unsatisfiable sentence, then we need to backtrack and try again with \(M\) assigned to false. If assigning \(M\) false also leads to an unsatisfiable sentence, then we’ll know that the entire sentence is unsatisfiable. In other words, we’ll now make two recursive calls to DPLL, one with \(M\) true and one with \(M\) false, and check if either one produces a satisfiable assignment.

On the first DPLL call on the branch with \(M\) true, we’ll add \(M\) true to our model, and use the simplified clause from the previous call:

- model: \(\{S:T, N:F, {\color{red} M:T}\}\)

- symbols: \([L, P, Q, R]\)

- clauses: \((M \vee Q) \land (L \vee \neg M) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\)

First, we simplify clauses by substituting in the new assignment (\(M\) true) from our model:

\[({\color{red} T} \vee Q) \land (L \vee {\color{red} F}) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\] \[(L) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\]With our new simplified clause, we check for early termination; as before, we don’t find it. However, we do find a pure literal, \(\neg Q\) (recall that since there are no instances of \(Q\) and only instances of \(\neg Q\), this counts as a pure literal). We set \(Q\) to be false so that \(\neg Q\) can be true and proceed.

On our second DPLL call on the branch with \(M\) true:

- model: \(\{S:T, N:F, M:T, {\color{red} Q:F}\}\)

- symbols: \([L, P, R]\)

- clauses: \((L) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\)

We simplify our clauses accordingly:

\[(L) \land (L \vee {\color{red} T}) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\] \[(L) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\]Checking for early termination and pure literals, we find neither. We do find the unit clause \((L)\) which we can then set to true.

On the next call in this same branch with \(M\) being true, we now have:

- model: \(\{S:T, N:F, M:T, Q:F, {\color{red} L:T}\}\)

- symbols: \([P, R]\)

- clauses: \((L) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\)

Let’s simplify our clauses:

\[({\color{red} T}) \land ({\color{red} F} \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee {\color{red} F})\] \[(\neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R)\]Checking for early termination and pure literals, we find nothing. When checking for unit clauses, we find \((\neg P)\). Let’s set that entire expression to true, i.e. setting \(P\) to false, for the next DPLL call.

Our next call proceeds as follows:

- model: \(\{S:T, N:F, M:T, Q:F, L:T, {\color{red} P:F}\}\)

- symbols: \([R]\)

- clauses: \((\neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R)\)

We simplify with \(P\) being set to false and get the clauses:

\(({\color{red} T}) \land (R \vee {\color{red} F}) \land (\neg R)\) \((R) \land (\neg R)\)

We check for early termination. We note that this sentence has both \(R\) and \(\neg R\), which cannot both be satisfied at the same time. At this point, we can say that this sentence is unsatisfiable.

Because the \(M\) true branch has ended in an unsatisfiable sentence, we backtrack to the point before assigning \(M\) true, and we make a DPLL call with \(M\) false instead. Our first DPLL call on the branch with \(M\) false:

- model: \(\{S:T, N:F, {\color{red} M:F}\}\)

- symbols: \([L, P, Q, R]\)

- clauses: \((M \vee Q) \land (L \vee \neg M) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\)

We simplify clauses by substituting in the new assignment (\(M\) false) from our model:

\[({\color{red} F} \vee Q) \land (L \vee {\color{red} T}) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\] \[(Q) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\]We aren’t able to terminate early, and we don’t find any pure literals. We find a unit clause \(Q\), so we make another call to DPLL with \(Q\) true (and removed from our symbols list).

Our second DPLL call on the branch with \(M\) false:

- model: \(\{S:T, N:F, M:F, {\color{red} Q:T}\}\)

- symbols: \([L, P, R]\)

- clauses: \((Q) \land (L \vee \neg Q) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\)

Substituting the new assignment (\(Q\) true) into our clauses:

\[({\color{red} T}) \land (L \vee {\color{red} F}) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\] \[(L) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\]We aren’t able to terminate early, and we don’t find any pure literals. We find a unit clause \(L\), so we make another DPLL call with \(L\) true (and removed from our symbols list).

Our third DPLL call on the branch with \(M\) false:

- model: \(\{S:T, N:F, M:F, Q:T, {\color{red} L:T}\}\)

- symbols: \([P, R]\)

- clauses: \((L) \land (\neg L \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee \neg L)\)

Substituting the new assignment (\(L\) true) into our clauses:

\[({\color{red} T}) \land ({\color{red} F} \vee \neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R \vee {\color{red} F})\] \[(\neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R)\]We aren’t able to terminate early, and we don’t find any pure literals. We find two unit clauses \((\neg P)\) and \((\neg R)\). By our variable ordering, we choose \(P\) first, and so we make another DPLL call with \(P\) false (and removed from our symbols list).

Our third DPLL call on the branch with \(M\) false:

- model: \(\{S:T, N:F, M:F, Q:T, L:T, {\color{red} P:F}\}\)

- symbols: \([R]\)

- clauses: \((\neg P) \land (R \vee P) \land (\neg R)\)

Substituting the new assignment (\(P\) false) into our clauses:

\[({\color{red} T}) \land (R \vee {\color{red} F}) \land (\neg R)\] \[(R) \land (\neg R)\]We check for early termiination. We note that this sentence has both \(R\) and \(\neg R\), which cannot both be satisfied at the same time. At this point, we can say that this sentence is unsatisfiable.

Because the \(M\) true assignment resulted in an unsatisfiable sentence, and the \(M\) false assignment resulted in an unsatisfiable sentence, we can conclude that this entire sentence is unsatisfiable, and we’re done.